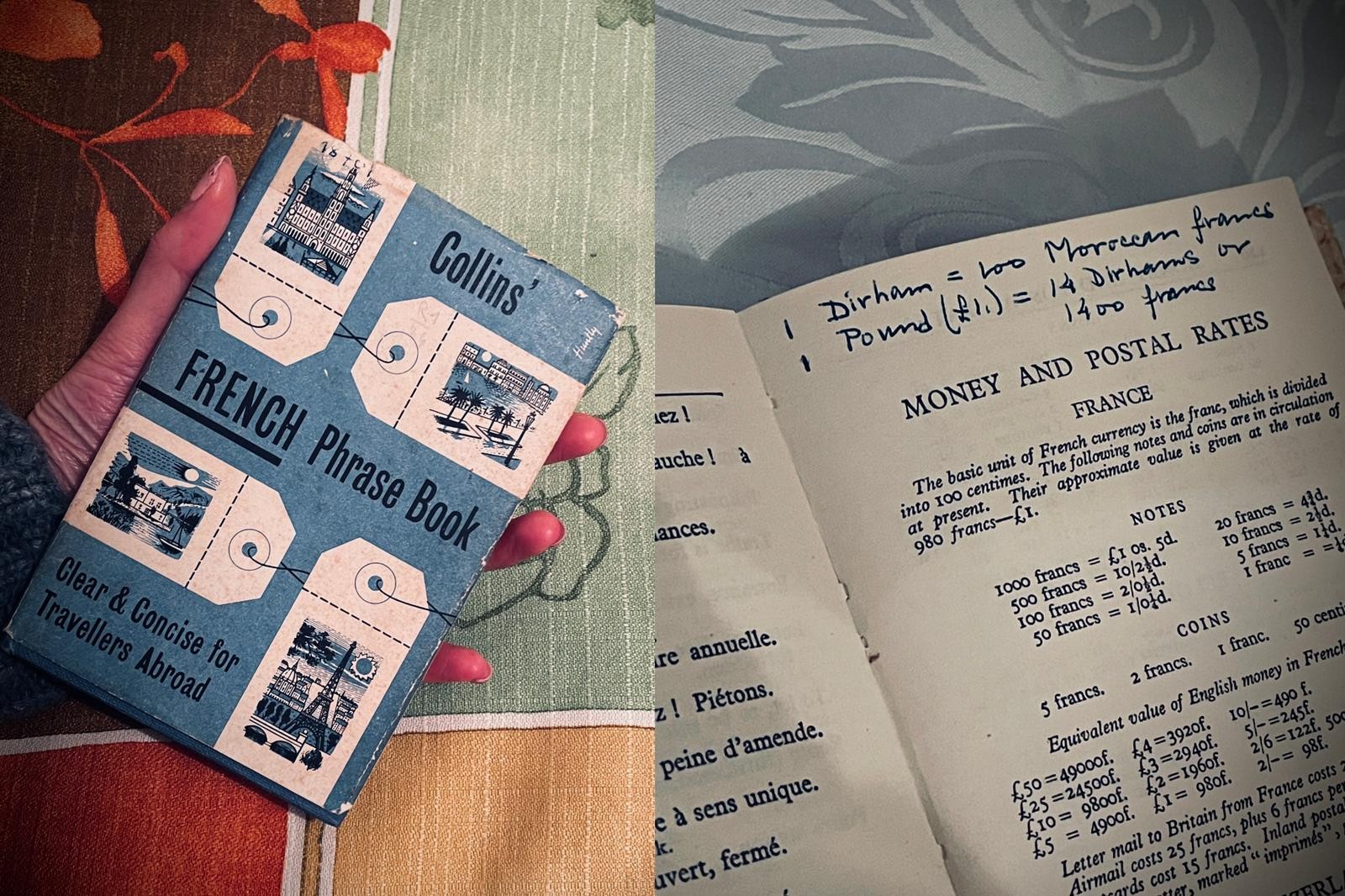

Tucked into an overflowing shelf on one of Rabat’s many bookstores was a second-hand pocket English-French phrasebook with yellowed pages and a smokey scent. The unexpected find, first published in 1950 by Collins and stamped for sale in 1964, offered me fascinating insights into the historical societies in Britain and France — and the travels that link them.

Of shillings and Moroccan francs

The book is listed with a price of “2s. 6d.” so I initially assumed the “s” to be a sterling pound. But further research revealed that “s” is in fact a “shilling” and “d” a “pence,” derived from Roman coin denominations “solidus” and “denarius.” The abbreviations appeared in the “Oxford English Dictionary” as early as 1387.

With each pound equivalent of 20 shillings and each shilling equivalent of 12 pennies (plural for pence), the book’s value would have been less than half of a 1950 pound. In 1971, the shilling was phased out of the pound system for the decimal system, but remains the basic monetary unit in Kenya, Somalia, Tanzania, and Uganda.

The book explains in detail the conversion from British to French money on page 125, but what caught my interest was the two lines of elegant handwriting scribbled in dark-blue ink, likely from the book’s previous owner: “1 dirham = 100 Moroccan francs; 1 pound = 14 dirhams or 1400 francs.”

Morocco had switched to franc in 1912 when the majority of its territories became a French Protectorate. The dirham was reintroduced in 1960 but the franc remained in circulation until 1974.

The note revealed that the book was most likely purchased and brought here because its owner traveled to Morocco and communicated through French during their stay. The coexistence of both dirhams and francs indicates that they likely traveled some time between 1960 and 1974.

On the topic of money, I must add in my own Morocco traveling tip: you may be told an absurdly high price for a simple item, but don’t fret. The shop owner likely gave you the price in “real” (from the Spanish system) so the dirham equivalent is one-twentieth of that.

‘I should like to see a mannequin parade of summer fashions’

The previous owner came from a society where “it is customary to raise the hat and preface any remark or inquiry with ‘pardon monsieur/madame/mademoiselle’,” the book’s preface details, hinting at an old-fashioned English society straight out of a period drama.

Here are some aspects of travel that the book deems necessary to translate but are antique curiosities today:

1. “telegram” and “cablegram”

2. “kodak films,” “negative,” “under-exposed,” and “over-exposed”

3. “gramophone records”

The text also reveals that a trip to France was very much a pleasure exclusive to the rich back in the day, as the accommodations they afforded and the activities they engaged in are eye-bogglingly posh. For example, hotels had “chambermaids” and included services to mend socks and dry boots for their guests.

The ladies’ fashions section was most dramatic of all, providing translations for “mother-of-pearl buttons” and “a straw hat with a veil” — which evidently must be carried in its own adorned box instead of just a bag.

The prevalent purchase of “talcum powder” for cosmetics is a concern, as later research has revealed its link to cancer, especially between talc with asbestos and lung cancer.

Yet no comment tops this in absurdity: “I should like to see a mannequin parade of summer fashions.” Imagine if you utter it today!

A somber history

Moving from the high society’s bourgeois lifestyle to the section “visiting battlefields,” I sobered from the reminder of a bitter history when most people alive in Europe had lived through one, if not two, deadly wars.

World War I between the Allies and the Central Powers embroiled both England and French, killing approximately 9 million soldiers on top of injuries and civilian casualties. World War II between the Allies and the Axis, with 70 to 85 million fatalities, the majority of which are civilians.

As such, English travelers to France likely had a personal history with the war, and thus would like to know how to say phrases like “front-line trenches,” “the black-out,” “the all-clear,” “an incendiary bomb,” “the ruins,” “barbed wire,” and “shrapnel.”

The lucky survivor may find themselves using the translation of “I was here in 1940; I am an old soldier” to recount his history to a former ally who fought on the French frontlines. They may also mourn the lives of people they once knew as they tell a wide-eyed French child that “eleven hostages were shot here.”

What has evolved and what stays the same

As someone from Gen Z, it feels surreal to extract details on how life was like from an old book I stumbled across. My amateur historical research, inevitably, leads me to some obscure words whose meanings were completely lost on me.

1. millinger: Google yields no answer. A little help here?

2. hosier: a seller of hosiery, meaning legwear. According to Google, the word was popular in 1800 but has since then declined greatly.

3. Whitsuntide: the weekend or week of Whitsun, the Christian holy day commemorating the Holy Spirit’s descent upon Christ’s disciples. Unlike the more widely known Christmas and Easter, the use of “Whitsuntide” as a word has also greatly declined since 1900.

But some things stay the same:

1. “someone (that man) has robbed me”

2. “that man is following me everywhere”

It’s been a journey reading this pocket phrasebook, so let me leave us English-speakers with a final oddity: a week in France consists of eight days — and two weeks are 15 days, somehow. Don’t ask me why.