In late June of 2022, media platforms High Line Art and Audemars Piguet Contemporary co-commissioned a tornado-like sculpture on the High Line in New York City on West 24th Street – a public park built on a historic railway stretching from Gansevoort Street to 34th Street on the West Side of Manhattan.

Made out of black foam, aluminum, and e-bike motors, the sculpture “Windy” almost seems like the artwork spins indefinitely. As the entire sculpture rotates through one big hidden motor, the thin black disks simultaneously spin from individual motors, creating a visual illusion.

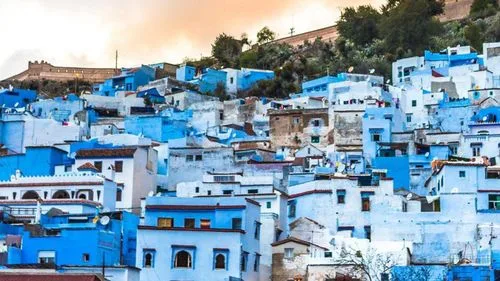

The visionary behind the work, Meriem Bennani – born in Rabat in 1988 and currently resides in Brooklyn, New York City – is a visual and animation artist. She obtained a Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) from The Cooper Union in New York in 2012 after receiving her Masters in Fine Arts in Animation from the Ecole Nationale Superieure des Arts Decoratifs in Paris in 2011. Bennani, like many minority artists living in the West, uses her personal experiences and artistic endeavors to approach life in terms of reality, identity, and cultural ideals.

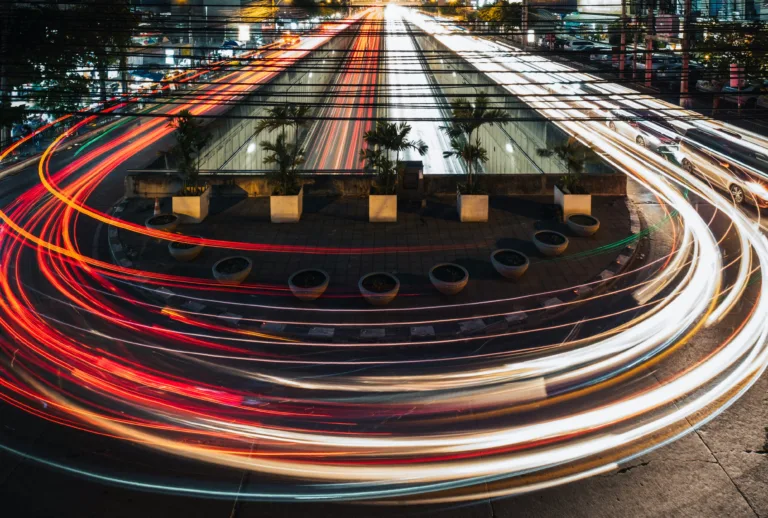

The train tracks that ‘Windy’ is situated on.

Bennani experiments with a variety of art mediums such as film, sculpture, social media, animation, and television. In her work, she tends to create art with humorous representations of the real-world and popular culture, an approach that allows her to take controversial ideas and manipulate them into works of art that tackle a deeper message.

Her more well-known projects have surrounded video art. She has collaborated with filmmaker Orian Barki on an episodic artwork titled “2 Lizards” – a sarcastic cartoon depiction of everyday life during 2020. It follows the lives of two animated lizards in the real-world – voiced by both Bennani and Barki – as they try to pass the time during quarantine. It is available for show in the Whitney Museum of American Art and Orian Barki’s website.

Since Bennani’s art mainly surrounds fantastical concepts and animation, “Windy” is one of her more abstract creations, and it is the first-ever sculpture she’s released. In an interview with The Architect’s Newspaper, Bennani admits that “you can’t see it [“Windy”] for what it is, you just see the movement visually. And that’s the same as the process of animation. But the process of making it is completely different.”

Her own interpretation of the creative process differs from the audience’s reaction to viewing the artwork. Bennani also discusses how she surpassed the challenges in the process of creating “Windy” allowing “the touch of absurd cartoonishness often seen in her animations to come through.” In other words, she believes that this tornado sculpture looks realistic yet flexible enough to convey various meanings among the High Line passersby.

The view when standing on the High Line on 24th Street.

Inspiring chaos

Bennani’s entire creative process with “Windy” differs from her usual multimedia projects. When assembling the sculpture on the High Line, Bennani and her crew could not bring the whole structure up in one piece. In an interview with Town & Country, she recalled the difficult moving process, explaining: “We had to assemble it part way, put it in a truck, and it on the elevators.”

Nonetheless, Bennani admired how throughout the installation process, strangers would stop and ask questions about “Windy” out of sheer admiration and curiosity. To Bennani, it is an entirely different experience when installing artwork in a public park rather than an enclosed museum.

The artist found herself in the midst of New York’s chaotic madness. That is why her intention of “Windy” is quite ambiguous: “I was walking on the High Line and realized I couldn’t make something still. I’d had the busiest year of my life and felt like the Tasmanian Devil, so I wanted to capture that.”

Bennani’s integration of animation and real-world contexts brings out a unique perspective in the art world. With “Windy,” “2 Lizards,” and many other projects, she has proven that art can and should be multifaceted. It is all right – maybe even recommended– to break through the barriers separating art and life to create something with interconnected and personal meanings.