Rabat – A souk vendor cuts open the plastic encasing a huge bale, revealing hundreds of pre-owned clothes shipped in from the West. He lays them out in a hap-hazard pile, naming prices without much regard for material or brand names.

The fact is, the secondhand clothing market is by no means a new phenomenon in Morocco. However, the concept that secondhand clothing can be sought after, and even the term “vintage” are not so familiar.

As a vintage enthusiast and newcomer to Morocco, my journey into the scene began with a casual Google Maps search for vintage clothing stores in Rabat.

Tucked away on the third level of an alley in the medina, OldSoul Vintage might be tricky to locate without the help of a kind shop owner on the bottom floor.

Making my way up, I was eagerly greeted by Said and Mustafa, who run the OldSoul Vintage store. Both of them are evidently hip, sporting hoodies and baseball caps. They sat down with me for a Morocco World News interview to talk about their journey in the industry.

The used clothing bales were how Said, 42, got his start in reselling clothing.

When he was eight years old, his father would make him sell baby clothes from the shipments to learn the basic ropes of business. Soon, Said recognized that some clothes held more value than others.

“I began learning the names of the [brands] that bring more money when I started skateboarding,” says Said.

“I started taking clothes from my father and selling them to my friends.”

One of those friends was Mustafa, 38, who founded OldSoul Vintage. He says that Said helps him man his shop.

“We would watch a lot of videos of people skateboarding and see the brands they wear, their style,” Mustafa said.

“We would go to the flea markets looking for those clothes to look like a pro — just pretending.”

Beyond brands, these two collectors know to look for certain labels, materials, and stitching — a skill developed with 20 years of experience — that indicate the age, quality, and rareness of a garment.

In 2016, Mustafa launched OldSoul Vintage as an online shop on Instagram. He hoped to reach customers from all over the country, even internationally, who recognized the value of the items he collected. Then, when he was formally prohibited from selling clothes on the street in 2017, he opened the physical OldSould Vintage store in 2021.

Vintage nautical artifacts decorating the walls add to a comprehensive feel of the shop, and the clothes come from all over — souks, flea markets, other vintage sellers in Morocco, and from Mustafa’s connections in Europe.

More than bales: importing clothes, ideas and education

The clothes themselves aren’t the only commodity being imported from the West. So seems to be the concept of vintage resale.

“I tried to find the same feeling that I got from the flea markets in France,” says Oliver, 49, organizer of Marché Vintage, a tri-monthly event in Rabat that brings together vendors from all over the country.

I came to attend the eighth Marché Vintage in February somewhat by chance. Two girls I ran into while leaving OldSoul Vintage shared the details for the market that Saturday when we started chatting after I complimented their unique style.

Speaking with a distinct north-of-Paris accent, Oliver explains how the market began in 2021 with just vinyls, but now features clothing, books, and several other items in flea-market fashion.

Marché Vintage at SOttoSOpra in Rabat in February. Picture by Sachi Akmal

Salma, 45, a vendor at the market, also attributes flea markets from her time in France as the reason she became interested in reselling. However, she claims that Morocco still needs a lot of time to warm up to the concept, especially in cities that are not as “Westernized” as Rabat.

In trying to understand why there’s generally a stigma surrounding secondhand clothes, several people I spoke to hinted at — paradoxically — European influence.

Morocco’s history as a former French colony undoubtedly instilled an esteem for the wealthy European look. New clothes signify wealth while old clothes signify a disregard for superstitions.

“But I think the mentality, especially with younger people, is changing,” suggests Oliver.

“People are not ashamed now to come here and buy old stuff. And in my small, small way, I want to help push them gently in this direction,” he added.

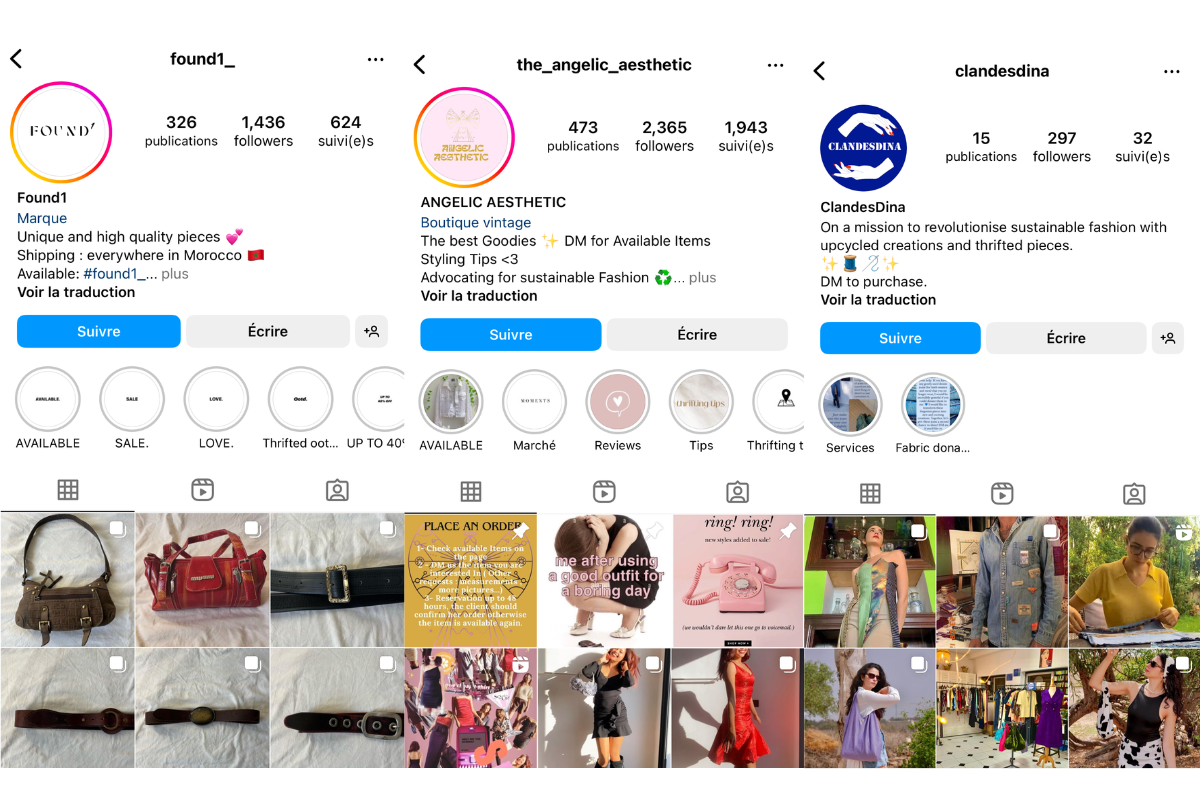

Reema, 24, owner of @Found1_ on Instagram, represents the younger demographic that makes up most of the clothing vendors — and customers — at the market.

Upon hearing that I was American, she declared, “Yes, the influence is coming from the US. This is why people are getting more interested in [vintage clothing].”

I asked her whether she thought social media platforms, such as Instagram and TikTok, were responsible for this shift.

“Exactly! This is exactly the reason. People are, you know, influenced — and this is a good influence.”

Malak, 23, owner of @The_Angelic_Aesthetic on Instagram, raises another aspect crucial to the recent revival of vintage clothing: education surrounding sustainability.

“Actually, I went on a double-degree program to Finland. There, they have a lot of big sustainable shops — you know, thrift shops but in a more formal, curated way. I was kind of into it and I ended up doing my thesis on textile and circular economies,” says Malak, who also shares that research in this area is increasing in Morocco.

The rise of fast fashion has contributed to an excess of clothing that plagues not only Western markets, but the Moroccan market as well. Many vendors said that finding true vintage, high quality items these days meant sorting through mostly fast fashion clothes in the bales.

A common phrase I heard among resellers was giving their clothes “another life” — contributing to the circular economy and combating the environmental impact of overproduction. They use terms like “vintage,” “sustainable,” and “pre-loved” to reframe the perception of used clothes and reflect the benefits of shopping secondhand.

An economic means, but not a livelihood

“In 2020, since I had nothing to do pretty much, I got interested in bags— ” explains Reema before she cuts herself off to state the price of a shirt a customer is motioning at.

“I started looking for them in bales and souks. And this is where it started. I thought about making a business, making money out of what I like.”

This is how most of the 20-something vendors I spoke to got their start: during quarantine. Many of them full-time students, reselling clothes became an enjoyable side-hustle to help support themselves while pursuing an education.

However, the costs for them have increased as well.

“I find [bales] to be more and more expensive these days. Before Covid, you could find items for one dirham, but now the price has exploded. You can find a shirt for 80 dirhams. Going from one dirham to 80—it’s not very expensive, but to me it’s very shocking,” says Dina, 25, owner of @Clandesdina on Instagram.

Most vendors stick to their online shops, where they report most of their revenue coming from, along with occasional pop-ups such as the Marché Vintage to allow customers to see and try on their items. They display QR codes to direct customers to their Instagram shops.

“I would love to [open a store] one day but I’m not sure. I think in Morocco we still have years to come before I’d really be able to make a profit by opening a store,” says Malak.

“I do this business because I like it,” states Mustafa.

Then he laughs, “But for making money, it’s not a good idea. You should do something else. It costs me too much money to rent a store, and rent a house because I’m not living with my parents.”

He’s also less optimistic, 20 years into the industry, about the increasing popularity of vintage clothing in Morocco, claiming only 10 to 15% of the Moroccan population is even aware of what the term “vintage” means.

Despite everything, he has stuck with the business due to something I observed in every seller I spoke to: a passion for clothes.

On my walk home one day while writing this piece, I came across a store I had never seen open before. The careful arrangement of unique jackets, shoes, and jewelry signaled clearly that it was a vintage store. I stepped off the sidewalk to catch the name of it, but found none.

Inside, a middle-aged woman quickly awoke from her nap and greeted me, bringing my attention to various items around the store — their brand, material, and features.

Her fondness for each item was evident. I thought of Dina, who mostly sells her grandmother’s old clothing and loves sharing the story behind each item — a reminder that the clothes are not just pre-owned, but pre-loved.

“What is the name of this store?” I asked.

“Oh, everyone around here knows me, they just refer to my shop by my name — Nadia,” she replied cheerfully.

I smiled. There’s something charming about forgoing the first step in marketing a business. Whenever she chooses to open her doors, Nadia lets her curated display speak for itself.

The business she has chosen might be gaining popularity in Morocco, but she doesn’t seem to care — she’s doing something she enjoys.