In a multidisciplinary finissage event, MMVI showcased the intellectual and artistic exchange between Moroccan artists and the mid-19th century CoBrA movement.

Rabat — The Mohammed VI Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rabat is marking the end of its current exhibition “CoBrA: A Multi-Headed Snake” which closed its doors this past week. The event included a guided tour of the galleries, a presentation on the work of CoBrA artist Pierre Alechinsky, and a poetry performance.

The exhibition opened this past October with the aid of the Dutch, Belgian, and Danish Moroccan consulates, as well as the National Foundation of Museums. The exhibit was the next step in a growing relationship between the MMVI and the Dutch CoBrA Museum in Amstelveen. Their first collaboration took place in 2022 when the MMVI lent the CoBrA Museum a significant portion of their collection for their exhibition on Moroccan modernists: “The Other Story: Art from Moroccan Modernism.”

For their 2024-2025 exhibition circuit, the CoBrA Museum has returned the favor, lending Mohammed VI over 100 works from their collection.

Leon Buskens, director of the Dutch Institute of Morocco (NIMS) a key organization in the realization of this collaboration, remarked on its future implications. “Morocco is in this exchange process with museums abroad, with museums in Spain, in France, and now,” he said. “This exchange between Morocco and the Netherlands is part of a much bigger project.”

Alongside the CoBrA exhibition, the MMVI originally opened “Chaibia/CoBrA: Au Croisement des Libertés,” in December 2024. The exhibition draws lines between prolific Moroccan painter Chaibia Talal and the largely European CoBrA movement.

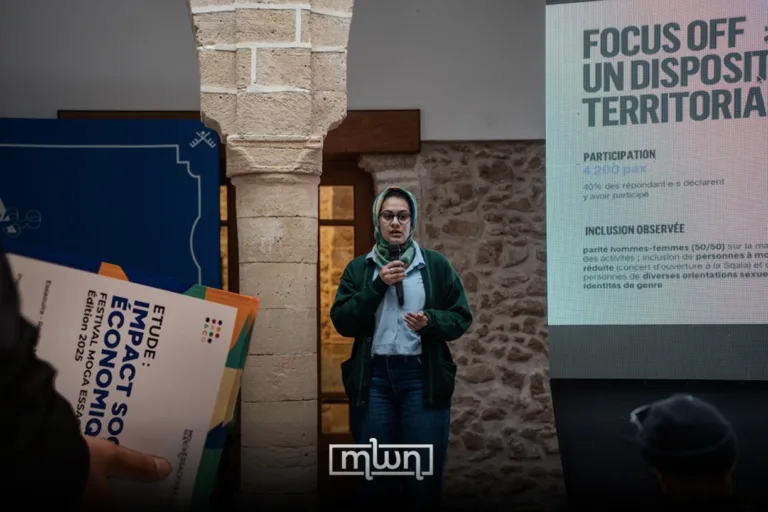

During her talk, “CoBrA et le Maroc: Influences et inspirations,” Louise Witjnberg, conservator and art historian specializing in the CoBrA movement, reinforced these connections between North Africa and CoBrA.

“What Dr. Weinberg showed in her lecture is that there were these exchanges, but that it was not only artists from West Western Europe visiting North Africa, but also the other way around,” said Bushkens.

Houda Kessabi, a coordinator of the CoBrA exhibit, remarked on the importance of spotlighting this relationship and bringing this interchange into the present day.

“This assertion of creative freedom to the detriment of conventional codes established by the classical school, and outside of the discourse around abstraction/figuration, is very important when it comes to Moroccan art, which has known important periods proclaiming this freedom to create outside of the lens of the colonial school,” Kessabi said in an interview with MWN. “Our artistic history goes perfectly with this spirit of assertion conveyed by the CoBrA movement.”

Still, Kessabi maintains that it is important not to retain the distinction between the artists associated with CoBrA and Chaibia herself.

“The link between Chaibia and the CoBrA movement was created by art history through critique; there is not a moral link,” Kessabi told MWN. “Chaibia never claimed to be a part of this movement, nor to adhere to its avant-garde or assertive spirit. For her, the creation should be, first and foremost spontaneous and free.”

CoBrA emerged as a joyful turn to spiritual and artistic freedom following the devastation of the Second World War. The name is a combination of the first letters of the European cities where this movement originated in 1948 – Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam. Though short-lived and largely based in Europe, the group crossed national borders and centered a spirit of interdisciplinary collaboration.

During the finissage event, Catherine de Braekeleer, honorary director of the Center of Engravings and Printed Images of the Louviere and expert on the CoBrA movement, walked visitors through the violent, contrasting, and dreamlike colors used by these artists and their rejection of established art historical tradition. Rather than a movement, she calls the it “esprit” (spirit), a choice that refers to the blurry temporal and geographical boundaries these artists often work in a “quatre mains” (four hands/duet) collaboration.

The exhibit and finissage paid homage to the multidisciplinary nature of CoBrA. Made up of painters and poets working in and across several mediums, the exhibit presented not simply paintings, but also archival materials — letters and publications — created by members of the movement to codify and disperse their political and artistic aims.

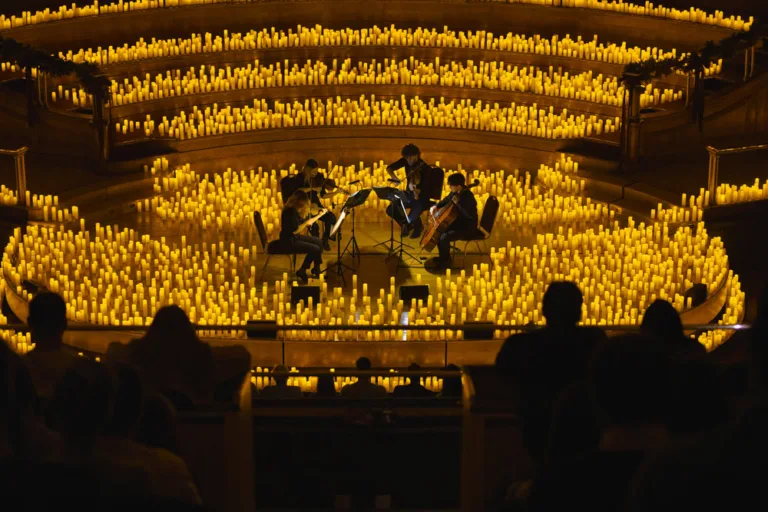

The finissage ended with a similar crossing of mediums, as a group of Moroccan poets took to the stage to finish the night with a collaborative performance. Each pulling from a specific artwork housed in the exhibition upstairs, the eight young poets gave voice to the static, silent work of the CoBrA artists in their performance “The Call of the Void.” Taking inspiration from artists working roughly 75 years prior, they transplanted the movement into a modern Moroccan context.

“What if these paintings left the museum at night,” poet Oum Nassar Mamine asked the audience in a final poem, “And they would return drunk from the delicious act of mischief.”

The finissage and poetry performance come after a Study Day, a series of lectures hosted by the MMVI and open to the community. The incorporation of educational opportunities and young voices has been foundational for the programming surrounding this exhibition.

“The Foundation raises money for the democratization of art and culture. It has targeted young people in particular,” Safae Elamarti, head of communications and sponsorship at National Foundation of Museums, told MWN.

Concluding her interview with MWN, CoBrA coordinator Houda Kessabi spoke to the museum’s continued goal to support these values. “Within MMVI we believe that success is more qualitative than quantitative,” she said. “We have fully fulfilled our objective when we meet with school children who become aware of the CoBrA movement and who remember the names of certain artists or who try to draw like them.”