At the Fez Music Festival, Miguel Poveda connected the dots between Federico García Lorca, flamenco’s Moorish soul, and the shared rhythm of Spain and Morocco.

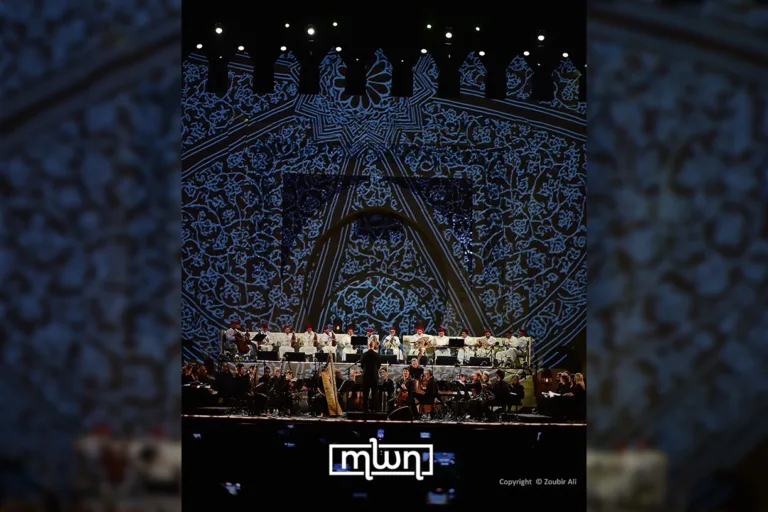

Fez– On a sunny afternoon in Fez, ahead of his performance at the city’s world-renowned Festival of Sacred Music, Spanish flamenco artist Miguel Poveda leaned into a conversation with Morocco World News that felt less like an interview and more like a reverent love letter to poetry, to heritage, and to the silent threads that connect Morocco and Spain.

“I don’t just read Lorca,” he said. “Sometimes I sing him.”

It sounds metaphorical, until you realize it’s literal. For Poveda, Federico García Lorca’s poetry is inherently musical.

“The way he writes, he was a musician too, you hear it. In your head, in your heart. “Poema del Cante Jondo” is a very musical book. I catch myself singing it out loud without meaning to.”

It’s the kind of statement that makes you realize Poveda doesn’t perform flamenco. He lives inside it. And when it comes to Lorca, a figure he calls “a god”, that devotion deepens into a sense of responsibility.

“Flamenco is sacred. Lorca is sacred. So the responsibility of interpreting him is massive. But at some point, you stop holding your breath. You recognize the emotional landscapes, the familiar music, and you realize: you’re part of this story too.”

Poveda describes this transition with a poetic metaphor: a bird that you decide to ride. “You fly with it,” he said. “And then things start happening. You begin shaping your own language within his universe, and what comes from your heart and head feels authentic.”

That authenticity is something Poveda refuses to compromise, not on stage, not in memory. Which is why he’s been personally involved in preserving Lorca’s physical legacy.

In the heart of Granada, he discovered a home where Lorca lived as a teenager, unmarked, forgotten.

“There was no plaque. Nothing. Just a building. And for those of us who love Lorca, it felt like a gaping absence,” he said.

So he did something about it. Poveda rented a space within that very building, where young Federico once played, where the fountain he wrote about still stands, and began a campaign to restore Lorca’s presence in the public eye.

“People should come to Granada and know: this is where he lived, where he gave a lecture, where he found inspiration.

I want the streets to speak his name again,” he said. “Others are working on this too, but to contribute even a little, it’s a personal joy.”

That same reverence threads through his reflections on Morocco. Asked about the cultural exchange between the two countries, his answer is immediate and passionate.

“Flamenco has Morocco inside it. Eight hundred years of shared history in Andalucía, how could it not?”

To Poveda, flamenco is a cultural cocktail of profound complexity. “Greek, Mediterranean, Moorish, Romani, Andalusian campesinos. it’s all there.

It all lives in flamenco. That vocal style? It’s you. It’s your music, your spirit. We don’t have to force it. It’s already married. It’s already home.”

He speaks of the cities of Andalucía with affection; Córdoba, Seville, Granada, and sees their reflection in Fez.

“Walking through the Medina today, I kept thinking: this is Granada. The artisan jugs, the pottery, the tiny alleys. It’s what we’ve called ‘ours’ for so long, but when you see it here, you realize where it truly began.”

Even the mosque towers of Fez, he noted, reminded him of Seville’s Giralda and the Torre del Oro. “Fez feels like an even more morisca version of Andalucía.”

Poveda’s words cut through borders with the same fluidity as his music. “When people live together, when they create together, there’s no race, no religion, no gender, no labels.”

“There’s just art. And art, when it’s free, is an explosion. A beautiful one.”

In his performance that evening, that explosion was palpable. His voice, at once fierce and delicate, seemed to float over centuries of cultural memory, braiding Andalusian sorrow with Moroccan soul, flamenco rage with Lorquian longing.

He doesn’t need to shout his reverence; it hums in every note, every gesture. Miguel Poveda is not just an interpreter of flamenco.

He is one of its living links, a singer who traces invisible histories with sound and makes them feel eternal.

As Fez continues to be a meeting ground for sacred music from around the globe, Poveda’s presence this year was not just a performance. It was a cultural reunion. A reminder that Spain and Morocco, despite their borders, remain two faces of the same artistic mirror.

And perhaps that’s why Lorca’s poetry still sings. Because in voices like Poveda’s, it doesn’t echo in the past. It lives in the now.