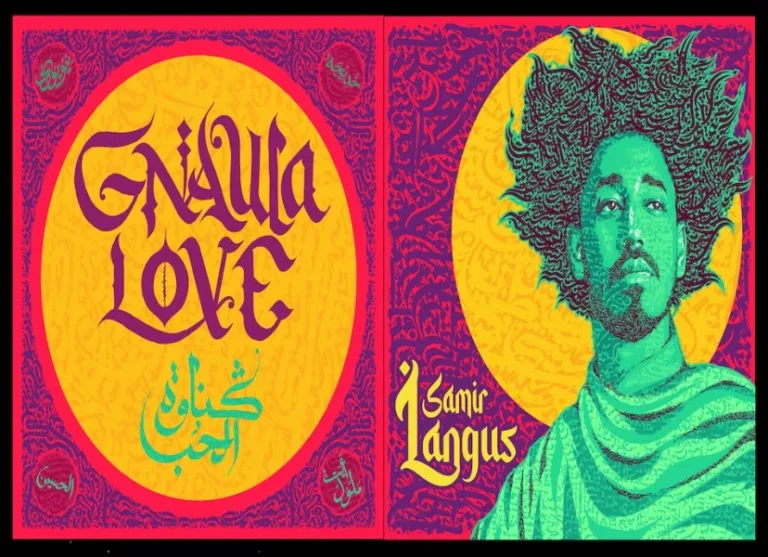

Born in exile and rooted in healing, Gnawa is Morocco’s most mystical musical legacy.

Fez– Gnawa music has long captivated visitors to Marrakech’s famous Jamaa el-Fna square and the vibrant Essaouira festival scene.

But beyond the rhythmic charm lies a complex, often misunderstood history, one that stretches deep into Africa and speaks of migration, memory, and spiritual healing.

The roots of Gnawa music trace back to sub-Saharan Africa, specifically the region once ruled by the great empires of Mali, Senegal, Guinea, and Niger.

Many Gnawa musicians are descendants of enslaved Africans brought to Morocco during the Saadian dynasty.

Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur, after his successful campaigns in Timbuktu in the late 16th century, brought back thousands of captives, many of whom worked on sugar plantations near present-day Essaouira or served in the royal guard.

Over generations, their cultural and spiritual practices blended into Moroccan life, giving rise to what we now call Gnawa.

Interestingly, the etymology of “Gnawa” remains uncertain. Some scholars suggest it stems from the Amazigh expression “Akal n Iguinawen,” meaning “land of the black people.”

Yet no definitive historical evidence confirms this. What is certain is that Gnawa culture does not belong solely to one ethnic or racial group.

It has drawn in Arabs, Amazigh, and sub-Saharan Africans, people of different backgrounds united by music, ritual, and ancestry.

These communities established familial schools of Gnawa practice, preserving the tradition and passing it down through generations.

Major spiritual lodges (zawayas) emerged in Marrakech and Essaouira, notably around the tombs of Sidi Abdellah Ben Hussein, Moulay Brahim, and the famous sanctuary of Sidi Bilal, named after the first mouazin in Islamic history and now considered the spiritual home of the Gnawa.

The influence of Gnawa music stretches beyond Morocco’s borders. It shares affinities with other North African spiritual traditions like Algeria’s Diwan, Libya and Tunisia’s Stambeli, and even diasporic African religions such as Haitian Vodou, Cuban Santería, and Brazilian Candomble.

All carry echoes of the same spiritual vocabulary, rooted in healing, trance, and ancestral reverence.

Gnawa ceremonies, known as “Lilas,” take place overnight and follow a structured ritual known as the “Derdeba.”

The ritual unfolds in three stages, “Al-‘Ada”, “Ouled Bambara” and “The Kings”. Each phase deepens the participants’ emotional and spiritual engagement, culminating in ecstatic trances believed to cleanse the body and soul.

Music is the lifeblood of this process. The Guembri, a three-stringed lute, anchors the sound, while metal castanets called “qraqeb” and hand clapping regulate tempo and energy.

Songs are passed down orally, often referencing spiritual entities, ancestral pain, and redemption. The music’s structure is pentatonic, but with surprising modal shifts that echo the nuances of Andalusian traditions.

And though the rhythms may sound repetitive, their hypnotic pull is anything but simple; they are crafted to guide the listener into altered states of consciousness.

Despite its deep historical roots, Gnawa music was not professionally recorded until 1975. Since then, its global influence has expanded dramatically.

Moroccan fusion groups like Nass El Ghiwane pioneered Gnawa’s incorporation into modern styles, while international icons like Santana, Robert Plant, and Peter Gabriel have collaborated with Gnawa masters, drawing connections between blues, jazz, reggae, and the mystic African core of this tradition.

Each June, the Gnawa and World Music Festival in Essaouira celebrates this legacy, drawing scholars, musicians, and spiritual seekers from around the world.

But beyond the concerts and cultural showcases, Gnawa remains, at heart, a music of survival and spirit, born from trauma, but sustained by joy.

It is, quite simply, the sound of memory healing itself.

Read also: Louvre Museum Shuts Down in Protest Against Overtourism