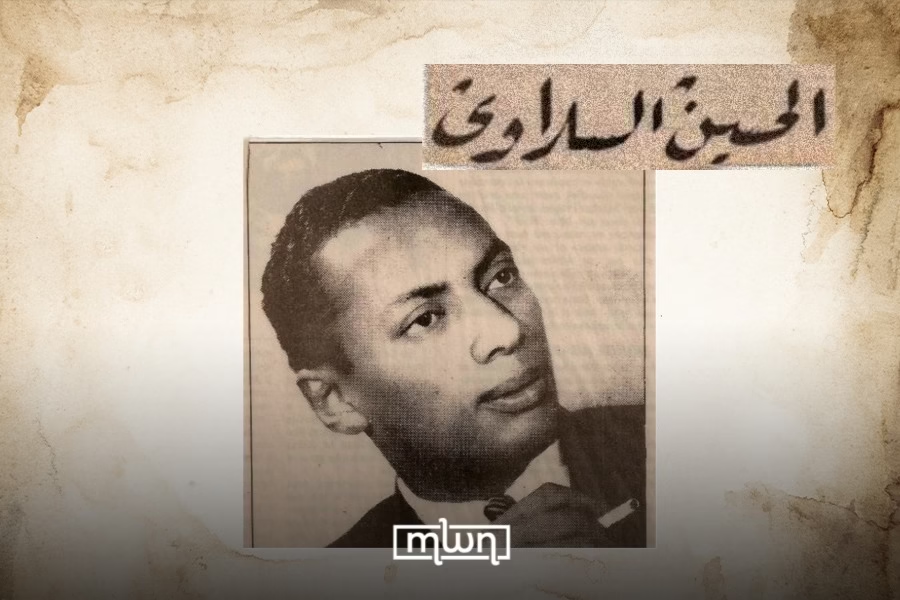

When American troops landed in Morocco, Hussein Slaoui responded not with protest, but with a sharp and clever song.

Fez – When American soldiers landed in Morocco on November 8, 1942, as part of the Allied operations during World War II, they didn’t just bring military gear.

They brought dollars, candy, cigars, and a sudden shift in local culture that didn’t go unnoticed.

One man, the legendary Moroccan artist Hussein Slaoui, took it all in and responded the way only he could: through a deceptively cheerful, cleverly satirical song.

In a recent reflection, Moroccan researcher Abderrahim Cherad revisited Slaoui’s lesser-known classic “El ‘Ayn ez-Zarka” (The Blue Eyes). While lighthearted on the surface, the song was, in fact, a sharp commentary on the cultural consequences of that historic moment.

First performed in 1943 and recorded on vinyl in 1945, the song remains a masterclass in social observation, wrapped in humor and melody.

The song opens with what seems like a compliment:

“Zin w l-‘ayn ez-zarka, jana b kul khir… lyom yemshou b l-ferqa, bnatna fi khir.”

(“Beauty and blue eyes brought us all kinds of good… now they leave, and our girls are doing just fine.”)

But as Cherad explains, this is no innocent praise. It’s sarcasm at its finest. Slaoui cloaked his criticism in a sugary tone, “wrapped in transparent cellophane,” as Cherad beautifully puts it.

What the singer was pointing to was the sudden obsession with the American soldiers; particularly their looks, their charm, and the material comfort they represented.

In the chaos of war, Slaoui saw something else unfolding: a society, being swept up in a wave of foreign infatuation.

“Chhal men hiya ma‘chouqa, darou liha chan l’marikan” (“So many women became sweethearts, given attention by the Americans”), he sang.

And the word that captured this surrender? “OK.”

“Ma tsma‘ ghir OK… OK… hada ma kan.”

(“All you hear is OK… OK… that’s all there was.”)

The Americans, with their movie-star charm and bulging pockets, created a stir wherever they went.

Streets once familiar became playgrounds of distraction. Even the older generation wasn’t immune. One of the most biting lines in the song points to the transformation of older women:

“Htta men l-‘ajayez chraw l-foulard.”

(“Even the elderly women bought scarves.”) Another line went even further:

“Htta men l-‘ajayzat lyom ychrabou r-rom.”

(“Even the old women today are drinking rum.”)

What Slaoui observed was a social fever that spread quickly. With American soldiers everywhere, their presence was impossible to ignore.

They handed out sweets, cigars, and dollars:

“Farqou l-fanid w s-sigar, zado dollar.”

(“They gave out candy and cigars, and added dollars on top.”)

It wasn’t just charity, it was seduction. Money spoke louder than tradition.

Public life shifted. In cafes, buses, even the humble “vélo-taxi,” a bicycle-powered cart for two, American soldiers were now part of the daily scene.

The song mentions:

“Fi l-koutchi m‘a t-toubis, yemin w chmal ma tswach kelmti.”

(“In the carriage and the bus, right and left, my words had no value anymore.”)

Even transportation had its moment:

“Darou liha chan, velo taxi.”

(“They made it special, the vélo-taxi.”)

What makes Slaoui’s work so powerful is how it preserves the emotional atmosphere of a country undergoing rapid change.

There’s no finger-wagging, no moral sermon. Instead, there’s observation, irony, and a quiet kind of mourning, mourning not just for traditions disrupted, but for that Americanized version of Morocco.

Eighty years later, “El ‘Ayn ez-ZarKa” stands as more than a song. It’s a living archive. A reminder that art, when done right, doesn’t just entertain; it revolutionizes.

And Hussein Slaoui did all that, set it to music, and left us a record not just of history, but of how it felt.

Read also: The Ceramics Museum of Safi: A Silent Archive of Moroccan Craftsmanship