Fez — In homes, “zawiyas,” and courtyards across Morocco, Gnawa communities hold “lilas” —overnight gatherings where music and prayer aim to soothe troubled hearts. The goal is not to defeat a demon but to restore harmony between the person, the community, and the unseen world.

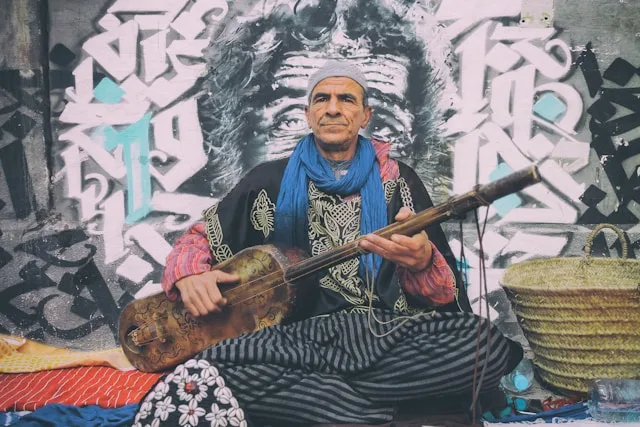

A lila is led by a “maalem” (master of ceremony) on the “guembri” —a three-string bass lute—with a chorus of iron “qraqeb” driving a steady pulse. A “moqaddema”—often a senior ritual guide—facilitates the night with incense, milk, and colored fabrics, inviting participants to step safely into trance, known as “jedba,” and then return to calm.

The ceremony moves through suites called “mluk,” each linked to a color, scent, and rhythm. White may open with mercy and purification, blue can evoke sea and travel, green hints at growth, and red calls courage. The heavy, cyclical beat associated with Sidi Bilal often closes the night, helping release fear and tension.

From the outside, lila scenes can look like exorcisms: swaying bodies, tears, laughter, and sudden stillness. Inside the circle, the language is one of service and reconciliation. The moqaddema reads breath and movement, adjusts incense or melodies, and works with the maalem to meet the person where they are.

Families who request a lila do not present it as a substitute for medical care. They describe it as spiritual therapy rooted in sound, repetition, and collective support. The rhythm entrains breathing, the community offers witness, and the shared script gives meaning to struggle and relief.

Gnawa culture is also a major artistic force. Masters collaborate with jazz, Afro-beat, and electronic musicians, and the Essaouira Gnawa and World Music Festival draws audiences from around the globe. In 2019, The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recognized Gnawa culture as “Intangible Cultural Heritage,” citing both its ritual role and musical innovation.

Visitors who are invited to a private lila are expected to dress modestly, avoid filming trancers, and follow the moqaddema’s lead. At public concerts, listening to the guembri’s low patterns and the qraqeb’s interlocking metal chatter reveals how call-and-response binds a crowd into one voice.

What endures is a simple promise: a night where music listens as much as it sounds, where pain is held rather than hidden, and where a person returns to the circle with lighter shoulders. In Morocco’s Gnawa tradition, healing is collective, rhythmic, and profoundly human.