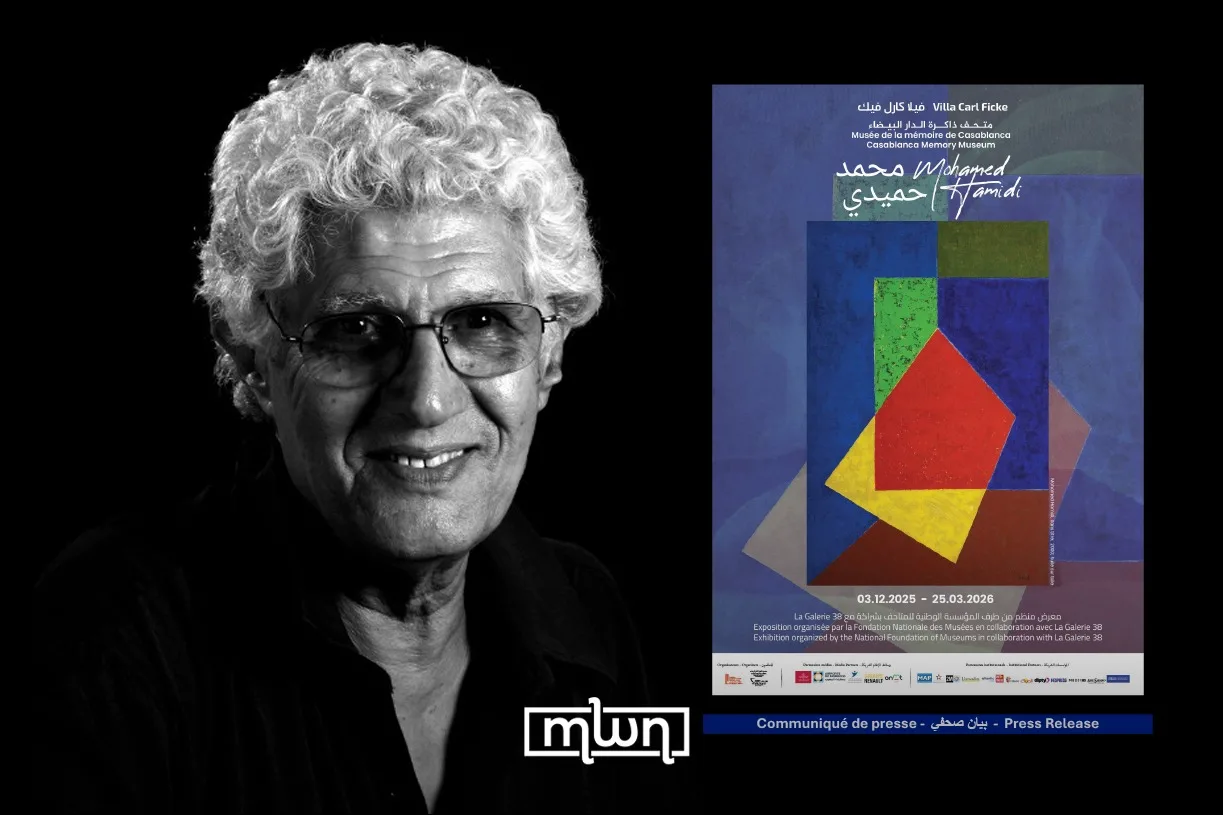

Fez — Villa Carl Ficke, home to the Casablanca Memory Museum, is hosting a major exhibition dedicated to Moroccan painter Mohamed Hamidi, running from December 3 to March 25.

The show invites visitors to rediscover the intensity and singular language of an artist who helped shape modern Moroccan art and whose influence now stretches well beyond the country’s borders.

Organized by the National Foundation of Museums in collaboration with “La Galerie 38,” the exhibition brings together a wide selection of works that span several decades of Hamidi’s career. The poster reproduced on the first page of the press dossier sets the tone: blocks of red, blue, green, and yellow interlock in a sharp geometric composition, hinting at his fascination with color, form, and abstraction.

A founding voice of the Casablanca School

Born in Casablanca in 1941, Hamidi belonged to the first post-protectorate generation to enter the city’s School of Fine Arts in the mid-1950s. He later continued his training in Paris, at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts (National School of Fine Arts) and the École des Métiers d’Art (School of Arts and Crafts) , at a time when Moroccan artists were actively negotiating their place between local traditions and international modernism.

From 1967 to 1975, he returned to teach at the Casablanca School of Fine Arts alongside Farid Belkahia, Mohamed Melehi, and Mohamed Chebâa. Together, they laid the foundations of what became known as the Casablanca School, a movement that sought to reconcile modernity with Morocco’s cultural heritage. Their 1969 “manifesto exhibition” on Jemaa El Fna square in Marrakech famously took art out of galleries and into public space.

Hamidi also co-founded the Moroccan Association of Plastic Arts (AMAP), helping to structure the visual arts scene at a pivotal moment in the country’s cultural history. His international recognition was cemented in 2019 when two of his works entered the collections of the Centre Pompidou in Paris — a rare distinction for a Moroccan painter of his generation.

From carpets and tattoos to a universal visual language

The curatorial text describes Hamidi as both “painter of the human body” and “painter of the symbol.” In his canvases, silhouettes and limbs often dissolve into signs, creating what he himself called “corps-signe” — body signs charged with layers of meaning.

He drew on traditional crafts, Islamic architecture, Amazigh forms, and wider African references, then pushed them toward abstraction and symbolism. Motifs taken from carpets or tattoo patterns reappear in his works, stripped of their original context and recomposed as part of a broader universal language.

Hamidi’s curiosity was not limited to Morocco. The exhibition notes point to his sustained interest in Egyptian and Japanese visual traditions. These influences, absorbed over years of research and travel, fed into a personal vocabulary that remained rooted in local memory while opening onto wider horizons.

Color as memory and matter

One of the recurring threads in the show is Hamidi’s obsession with color. The press material explains that he often prepared his own paints from natural pigments, searching for a precise “agreement” between tones.

On canvas, this takes the form of dense, matte surfaces where colors seem to vibrate against each other. Earthy ochres echo the soil of rural Morocco, while deep blues recall the artist’s childhood memories of sea and sky. The result is a chromatic world that feels at once intimate and monumental.

The exhibition at Villa Carl Ficke uses these contrasts to guide visitors through different phases of his work. Rooms move from more figurative compositions to pieces that verge on pure geometry, but the underlying concern with color and sign remains constant.

A posthumous tribute and a curatorial statement

Mohamed Hamidi passed away on October 6 of this year at the age of 84. The Casablanca exhibition is one of the first major tributes to his legacy since his death, and it doubles as a statement of intent from the National Foundation of Museums.

By dedicating a full museum program to a Moroccan modernist, the Foundation reaffirms its commitment to giving national creation a central place in its spaces. The press release notes that this show is part of a longer-term effort to highlight key figures in the country’s artistic history and to anchor their work in public memory.

For Casablanca, the choice of Villa Carl Ficke — a building already charged with the city’s layered history — adds another level of resonance. Hamidi’s abstract bodies and symbols now inhabit a site dedicated to urban memory, inviting visitors to see the city and Morocco’s modernity through his eyes.