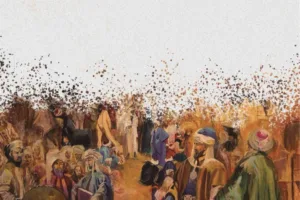

For centuries, Morocco’s traditional female performers have carried both the weight of heritage and the sting of judgment.

Fez – In Morocco, the word chiikha is loaded both with history and contradiction. It doesn’t just describe a profession. It describes a life shaped by rhythm, poetry, memory, and, all too often, judgment.

For centuries, the chiikha has been a central figure in Moroccan music and oral tradition, yet she continues to be met with discomfort, mockery, and moral suspicion.

These women are not just entertainers. They are storytellers. Their art, deeply tied to Morocco’s dialects and regional sounds, carries the weight of time.

Celebrated in private, judged in public

They’ve preserved voices that would have otherwise been lost. But instead of admiration, what they often get is ridicule.

The term itself has turned into a slur in many circles, used to belittle rather than recognize.

This stigma didn’t appear out of nowhere. It reflects a society that still struggles to reconcile public morality with cultural authenticity.

The chiikha appears at weddings, parties, and public festivities, bringing people joy and emotional release.

Yet that same public turns its back on her once the music stops. It’s a strange contradiction: celebrated in private, judged in public.

Much of this comes down to a misunderstanding of what the chiikha actually represents. She’s not just a dancer or a singer. She carries an entire oral legacy on her shoulders.

She memorizes complex poetic forms, adapts to different musical modes, and learns traditional instruments, all often without formal education.

The work demands talent, memory, presence, and years of dedication. But instead of recognizing the craft, society prefers to focus on her image.

The name chiikha itself has been bruised by time. It has been loaded with assumptions, twisted into a joke, or even used as an insult.

And worse still, some chikhate are publicly identified by nicknames tied to physical attributes or humiliating stereotypes, nicknames that follow them into recordings, event posters, and public discourse.

Imagine having your entire career stamped by a label you never chose, one that strips away your identity and replaces it with mockery. It’s more than offensive; it’s erasure.

Even within their own world, many chikhat end up isolated. Few marry outside the artistic circle. The profession itself is often inherited or entered through close-knit networks.

And while some adopt playful stage names to stand out, the public rarely sees this as artistic branding; it becomes yet another excuse to dismiss them.

At the core of all this lies a deeper issue: the tendency to equate artistic performance with personal morality. In the eyes of many, a woman who sings and dances in front of men must be doing something inappropriate.

Her visibility becomes a problem. Her voice becomes a threat. This reduction of a cultural practice to a moral debate is what keeps the chiikha stuck between admiration and disgrace.

Beyond the wall of resistance

There’s also the matter of class. The chiikha rarely comes from privilege. She usually comes from the margins: rural towns, modest families, and communities where oral tradition replaces formal schooling.

She doesn’t carry a degree, but she carries centuries of melodies. Her stage isn’t always a theater, it’s a wedding tent, a village square, a dusty festival ground. And that, in itself, is seen as less worthy.

The irony, of course, is that the same people who look down on the chiikha often rely on her to create the soundtrack of their lives.

She’s the one who turns silence into celebration, who fills the room with words and rhythm when there are no speeches left to give.

She transforms heavy moments into movement, pain into performance. Yet she’s never fully welcomed into the mainstream. She is heard but not listened to. Seen but not accepted.

In recent years, there have been small shifts. More visibility through media, more acknowledgment of folk traditions, and more attempts to reclaim the chiikha as a symbol of cultural resilience.

But these are still baby steps in a much longer process. The weight of old judgments still hangs heavy, and for every moment of recognition, there’s a wall of resistance waiting just around the corner.

Being a chiikha is not easy. It never was. But it’s one of the most profound roles in Moroccan cultural life.

The woman behind the song is more than a performer, she’s an archive, a vessel, and a force. And until we learn to see her beyond the stereotype, we’ll continue to lose more than we preserve.

Because when we silence her, we silence a part of ourselves.