Fez – Washington marked a quiet but meaningful cultural moment with an event dedicated to Hassan Ouakrim, the Moroccan choreographer credited with introducing Amazigh dance and music to US audiences in the 1970s.

Hosted by the Middle East Institute in partnership with the Embassy of Morocco, the program centered on a screening of “Les mille et une nuits berbères” by Moroccan American filmmaker Hisham Aidi, followed by reflections on Ouakrim’s legacy.

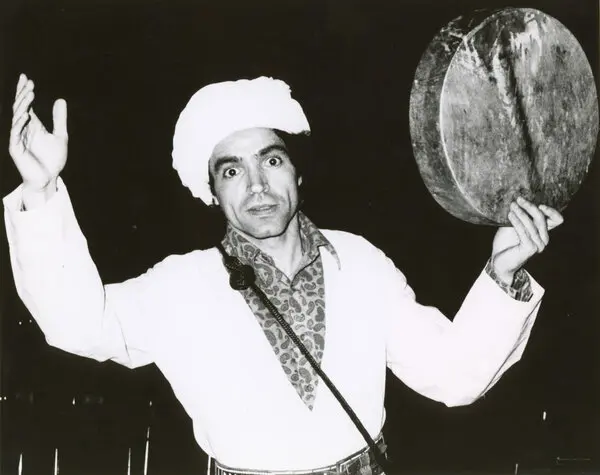

Arriving in New York at a time when downtown theaters were open to experiment, Ouakrim stepped into that energy with drum patterns from Souss and Saharan traditions and a movement vocabulary rooted in communal ritual.

On small black box stages and in lofts, he fused call and response rhythms with the improvisational freedom that animated the city’s jazz scene. The result was a conversation between North African forms and American avant-garde that felt both new and deeply grounded.

Read also: GUESS Celebrates its Roots in Marrakech

A turning point in his career came through his collaboration with Ellen Stewart of La MaMa, where Ouakrim developed pieces that set Amazigh dances like Ahwach and Guedra within bold theatrical frames.

Those works traveled across communities and introduced Moroccan sound and gesture to audiences who had never seen them live. Press notices from the time highlighted the charisma of a performer who could shift a room’s pulse with a drum phrase and a single ululation.

Aidi’s documentary gathers rare archival footage and testimonies to chart that path. It presents a young artist who linked Tangerine port cosmopolitanism to New York’s experimental nerve, and shows how those exchanges grew into long standing friendships with musicians who valued tradition as a living, changing force.

The film also traces a wider story of early Moroccan artists in the United States and the bridges they built between scenes that rarely met on equal footing.

The Washington tribute framed Ouakrim’s journey as a reminder that cultural dialogue often begins with one person’s curiosity and stamina.

By insisting that Amazigh music and dance could hold a main stage, he opened a door that others have since walked through. The evening closed on a simple note. A drumbeat, a chorus, and a room of people swaying together to a rhythm that needed no translation.