Fez — The origins of one of the most discussed music documentaries of the season can be traced back to Morocco.

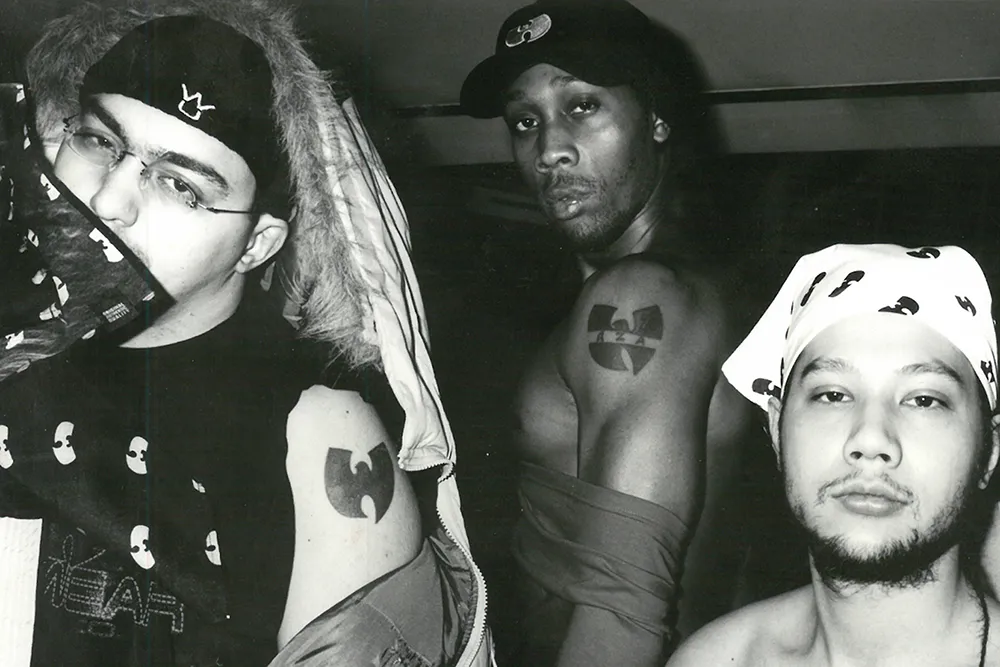

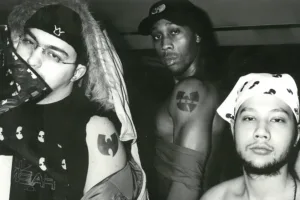

“The Disciple,” which premiered in world debut at the currently-running Sundance Film Festival in Salt Lake City, marks the feature-length documentary debut of British filmmaker Joanna Natasegara and revisits a little-told chapter of Wu-Tang Clan history through the singular trajectory of Dutch Moroccan artist Tarik Azzougarh, known as Cilvaringz.

Natasegara, who won an Academy Award in 2016 for “The White Helmets,” said the project was born during a family visit to Morocco, where she first encountered Cilvaringz. That meeting sparked the realization that a complex and largely misunderstood story within global hip hop culture had never been fully examined. What followed was a documentary shaped far from the conventions of American music cinema, guided instead by distance, restraint, and a refusal to simplify its subject.

From teenage devotion to Wu-Tang insider

“The Disciple” charts Cilvaringz’s improbable rise from a teenage Wu-Tang devotee in the 1990s to a trusted collaborator operating within the group’s inner circle under the guidance of RZA. The film presents obsession not as pathology, but as discipline, showing how sustained belief and relentless work can generate unlikely trajectories.

At the center of the documentary lies Cilvaringz’s role in the conception and execution of “Once Upon a Time in Shaolin,” a singular album produced in one physical copy and later auctioned for two million dollars. The project was conceived as a direct challenge to the commodification of music in the age of infinite digital reproduction, positioning sound as a rare and deliberate artistic object.

Art, controversy, and refusal of spectacle

The album’s legacy took a controversial turn when it was purchased by Martin Shkreli, a polarizing figure later convicted in a separate financial case. While this episode looms over the story, Natasegara has stated that she deliberately avoided framing the film as a moral reckoning or personal vendetta.

Instead, “The Disciple” focuses on the ethical and spiritual foundations of the Wu-Tang universe, emphasizing ideas of self-mastery, restraint, and purpose. The documentary resists the glossy tropes often associated with mainstream hip hop storytelling, favoring introspection over spectacle.

A cinematic language rooted in Wu-Tang aesthetics

Visually, the film draws heavily on kung-fu cinema and the iconography long associated with the Wu-Tang Clan. Archival material, historical audio, and carefully structured silences form a narrative built on duration rather than immediacy.

RZA appears primarily through archival footage, a choice Natasegara has described as essential to preserving the authenticity of his evolving philosophy rather than anchoring it to the present moment.

This approach allows each participant to retain complexity, avoiding heroic simplification or reductive critique.

Beyond Wu-Tang, a generational portrait

More broadly, “The Disciple” reflects on a generation shaped by 1990s ideals of perseverance, craft, and faith in long-term vision. Natasegara has argued that these values remain relevant for younger audiences navigating an era defined by speed, visibility, and constant validation.

By rooting its story in Morocco, hip hop mythology, and creative devotion, “The Disciple” emerges as more than a music documentary. It is a meditation on belief, artistic sacrifice, and the cost of pursuing meaning outside conventional success.