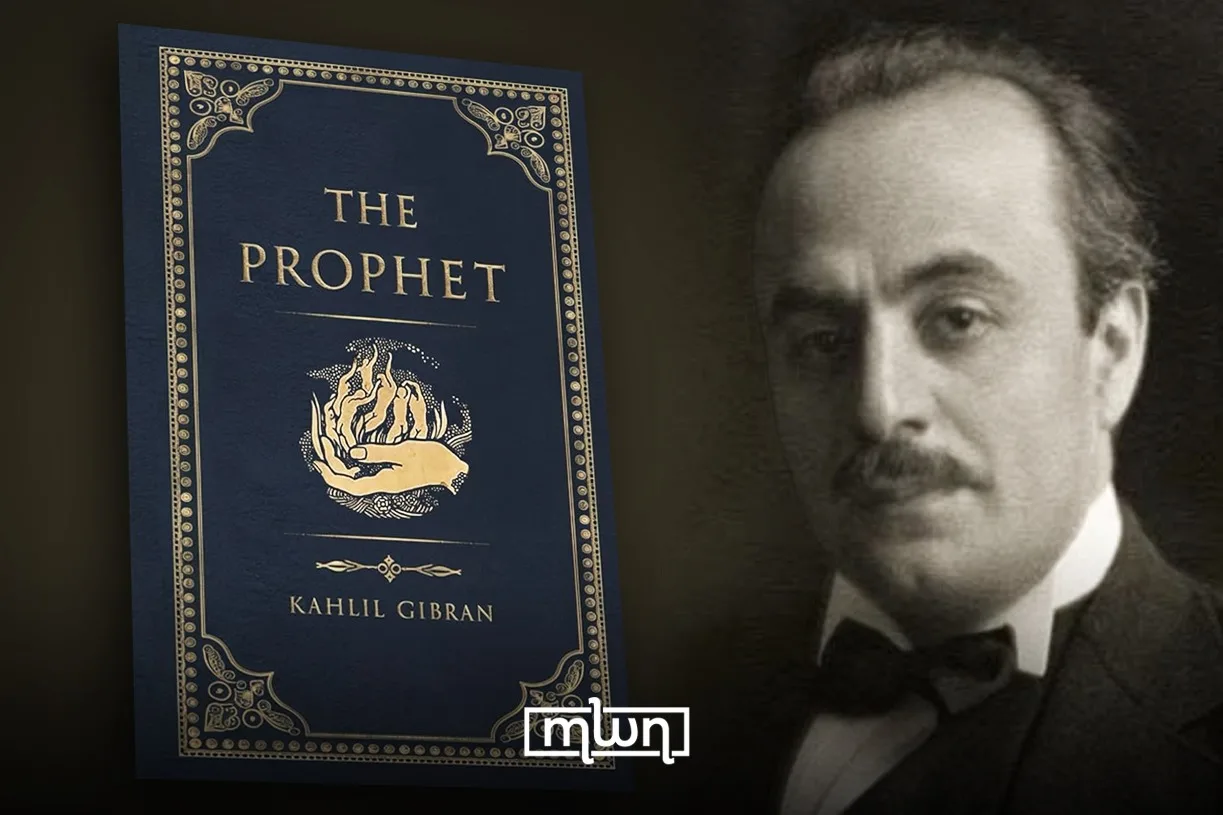

Fez — When Khalil Gibran published “The Prophet” in 1923, few could have predicted that the book would go on to sell millions of copies worldwide and become one of the most translated works of the 20th century.

Blending poetry, philosophy, and spiritual reflection, the book has never gone out of print. A century later, it continues to circulate at weddings, funerals, graduations, and quiet personal turning points.

Who was Gibran?

Born in 1883 in Bsharri, in modern-day Lebanon, then part of the Ottoman Empire, Gibran emigrated with his mother and siblings to Boston in 1895. The experience of migration shaped his worldview. He moved between East and West, Arabic and English, tradition and modernity.

Gibran was not only a writer but also a painter. He spent years in Paris studying art and later settled in New York, where he became part of the Arab-American literary circle known as the Pen League.

By the time he wrote “The Prophet”, Gibran had already published works in Arabic and English. But this book became his defining legacy.

Why he wrote ‘The Prophet’

Gibran reportedly carried the idea for “The Prophet” for more than a decade. He wanted to write a book that would distill universal spiritual truths into accessible language.

Professor Juan Cole of the University of Michigan has argued that Gibran offered “a dogma-free universal spiritualism” at a time when many readers were turning away from institutional religion.

Unlike rigid theological texts, “The Prophet” avoids dogma. Its structure is simple: a prophet named Almustafa is about to leave the city of Orphalese. Before departing, townspeople ask him about life’s essential themes — love, marriage, children, work, freedom, pain, joy, death.

Each chapter reads like a prose poem, offering reflection rather than instruction.

The timing matters. The book emerged after World War I, in a world grappling with trauma and disillusionment. Its message of inner wisdom and interconnectedness resonated deeply.

Why it is considered iconic

Several factors explain the book’s lasting status.

First, its language is simple but lyrical. Gibran writes in rhythmic, almost biblical cadences. The tone feels sacred without belonging to a single religion.

Second, the themes are universal. Love, sorrow, parenting, friendship, freedom — the book addresses experiences that cross cultures and generations.

Third, it arrived in the West at a moment of growing interest in Eastern spirituality. Gibran, as a Lebanese immigrant writing in English, bridged cultural worlds.

By the late 1960s, “The Prophet” found new life among countercultural movements in the United States. Its emphasis on love, self-knowledge, and freedom aligned with the era’s spiritual searching.

However, despite selling tens of millions of copies and never going out of print, “The Prophet” was largely dismissed by the Western literary establishment. As noted in a 2012 BBC World Service feature, many English professors regarded the book as simplistic and lacking literary depth, even while it became one of the most gifted and quoted works of the 20th century.

Some of its most enduring lessons

On love, Gibran writes:

“Love gives naught but itself and takes naught but from itself.”

Rather than portraying love as possession, he frames it as surrender and growth. Love, in his vision, both crowns and crucifies.

On children, he offers one of the book’s most quoted passages:

“Your children are not your children.

They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself.”

The lesson challenges ownership and control. Parents are described as bows from which children are sent forth as living arrows.

On work:

“Work is love made visible.”

In a few words, Gibran collapses the divide between labor and meaning, suggesting that purposeful effort is an expression of care.

On pain:

“Your pain is the breaking of the shell that encloses your understanding.”

Suffering, in his philosophy, becomes a pathway to awareness rather than something purely destructive.

Cultural and artistic influence

Gibran’s reach extends beyond literature. Musicians, spiritual teachers, and political leaders have cited him. John Lennon reportedly admired his writing. Elvis Presley was known to keep a copy of “The Prophet.” Indira Gandhi quoted Gibran publicly.

Writers such as Paulo Coelho have echoed similar themes of spiritual journey and introspection in their own work. Scholars often note parallels between Gibran’s aphoristic style and later self-reflective literary movements.

In 2014, the book was adapted into an animated film titled “The Prophet,” produced by Salma Hayek, further extending its global presence.

Passages from the book frequently appear in wedding ceremonies, memorials, and graduation speeches. Its language has entered everyday life, printed on greeting cards, inscribed in jewelry, and circulated widely online.

A legacy that endures

Gibran died in New York in 1931 at the age of 48. His remains were returned to Lebanon, where he remains a towering cultural figure.

More than a century after publication, “The Prophet” continues to move readers because it does not impose answers. Instead, it presents reflections that allow space for interpretation across cultures and generations.