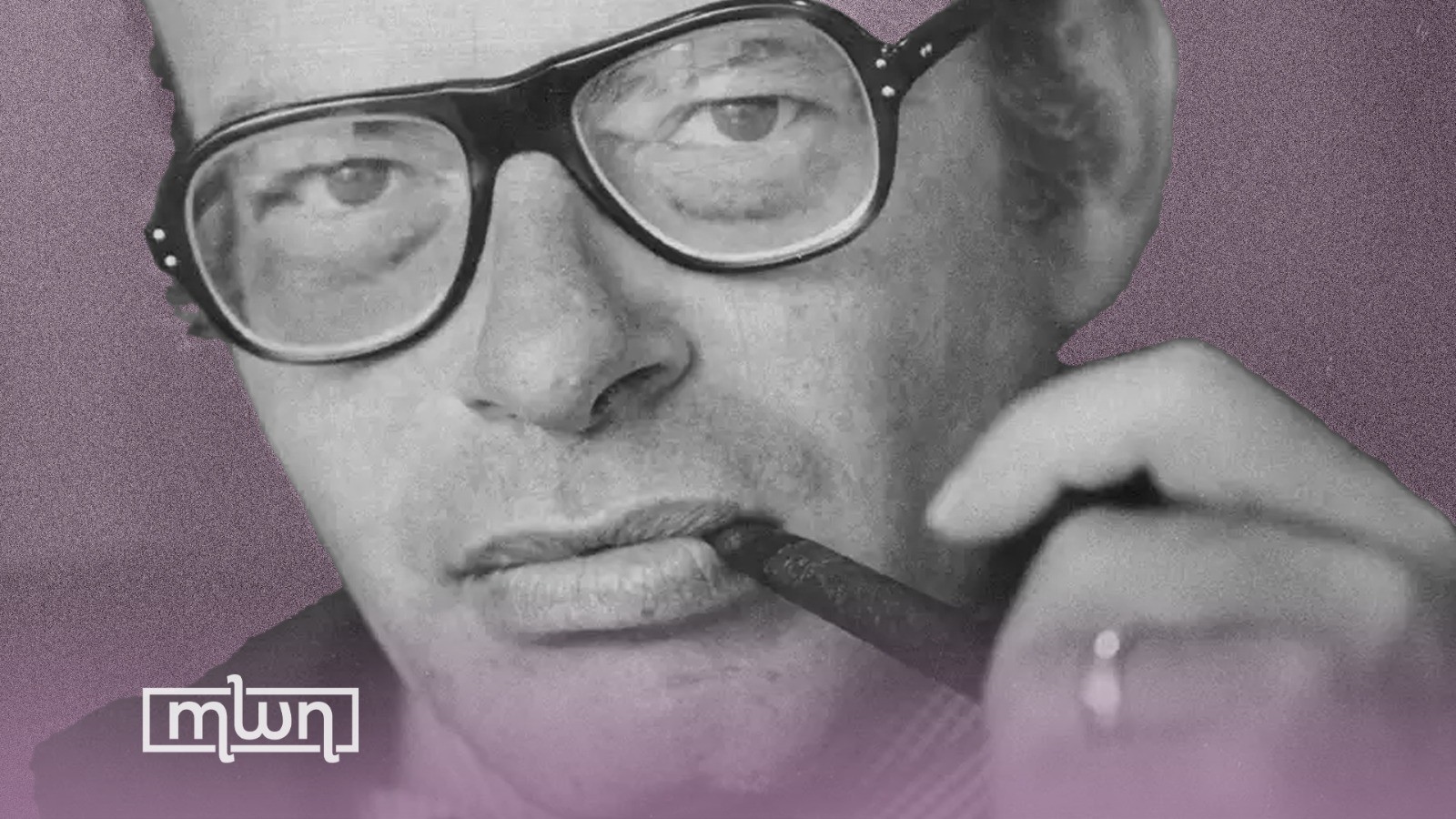

Rabat – In 1972, Rosenhan, a psychologist at Stanford University, with a penchant for shaking up the status quo, embarked on a daring experiment to assess the effectiveness of psychiatric medicine in treating mental illnesses.

Rosenhan and his seven friends, all doctors, a diverse crew of completely mentally healthy individuals, were armed with nothing but a fake symptom and a sense of adventure.

They entered the halls of psychiatric wards, eager to decode the enigmas of psychiatric diagnosis and expose the flaws in the system.

Their objective was to infiltrate the system, seamlessly blending in, and see just how “sane” they can appear.

Their strategy was simple yet audacious. Each member of the group presented themselves at multiple hospitals in five states throughout the United States, claiming to hear voices that echoed a hollow “thud” or whispered “empty.”

Normality’s porous borders

Once admitted, they shed their façade, behaving as they normally would, awaiting discharge under the guise of being “cured.”

From schizophrenia to bipolar disorder, the experts couldn’t see the forest for the trees, diagnosing them left and right with all manner of mental maladies.

Yet, despite their best efforts to blend in with the institutional backdrop, none were detected as imposters.

Even when they informed the doctors that they felt “fine” after supposedly receiving treatment and medication, specialists maintained that they needed more therapy,

The boundaries between sanity and insanity were not as sharp as society believed when this harsh truth became apparent.

After all, who’s to say what’s “normal” anyway?

In an interview with the BBC, Rosenhan revealed his astonishment, stating that he believed he would be allowed to leave the hospital anytime he wanted. Being “normal,” he said, he didn’t expect to be in the hospital for two months.

Rosenhan’s findings profoundly challenged the tenets of diagnostic procedures, sending shockwaves across the psychiatric industry.

The study highlighted the possible repercussions of mislabeling individuals based just on cursory observations and revealed the vulnerability of subjective evaluations in mental health assessments.

It was a wake-up call for a field whose foundation was the idea of distinguishing between sanity and insanity.

Beyond its academic significance, “Being Sane in Insane Places” serves as a thought-provoking commentary on the human experience.

The sensitive nature of our perceptions is shown by Rosenhan’s research, which shows how easy it is to make judgments and categorize people without seeing the complicated interplay of the human psyche.