What looks like a simple biscuit from Oujda or Safi began as a secret vessel for hidden gold.

Fez – In Morocco, kaak isn’t just a normal sweet. It’s a story. A quiet one, baked into the dough and passed from kitchen to kitchen, generation to generation.

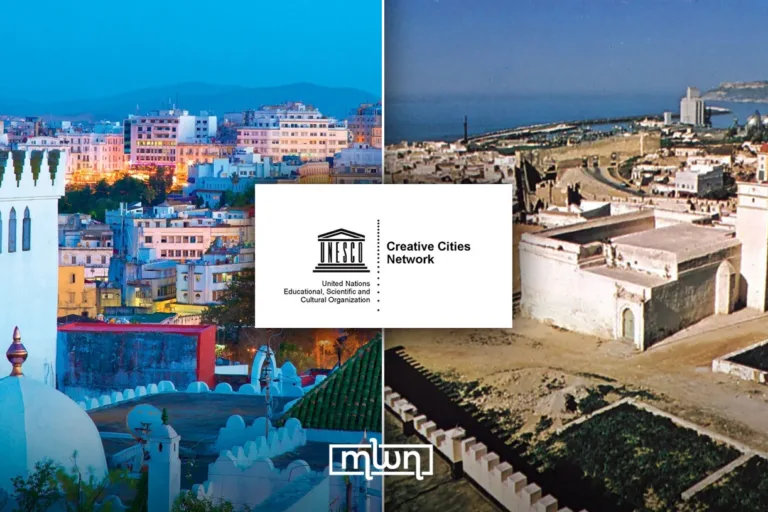

In cities like Oujda in the east and Safi by the Atlantic, this bracelet-shaped biscuit is a staple.

Locals call it “kaak oujdi” or “kaak mesfioui,” depending on where you are, but either way, it’s part of the culinary DNA of both regions.

It looks simple, just a golden ring of baked dough. But its shape has a past, and that past is anything but ordinary.

The origin of kaak traces back to the early 1600s, during one of the most painful chapters in Andalusian history.

When Spain’s King Philip III ordered the expulsion of Muslims who refused to convert to Christianity, those fleeing were forbidden from taking anything of value. No gold, no silver, no heirlooms.

But exile breeds ingenuity. According to historical accounts, Andalusian women began hiding their jewelry inside balls of dough.

They baked the dough slowly over low heat, making it look like simple travel provisions.

The bread passed unnoticed through Spanish checkpoints, and with it, their hidden treasures.

Read also: Five Senses Plan Reimagines Fez’s Restored Fondouks as Creative Hubs

An unlikely beginning

Once safely across the sea, many settled in Moroccan cities, including Safi, where the recipe evolved and stayed.

That’s the unlikely beginning of Morocco’s kaak: a biscuit shaped like the jewelry it once carried; a clever act of resistance turned into culinary tradition.

Today, you’ll find kaak on holiday tables, in market stalls, and inside tins passed around at family gatherings.

It’s still made the traditional way, with aniseed, sesame, and a hint of orange blossom.

Crunchy on the outside, soft in the middle, much like the story behind it.

Kaak isn’t just tied to Oujda and Safi by geography. It’s tied by memory. The two cities, one looking toward Algeria, the other facing the ocean, became keepers of this quiet legacy.

Every ring carries the weight of displacement, of resilience, of people who used baking as a way to hold on.

You don’t need to know the story to enjoy kaak. But once you do, it tastes a little different, more layered, more alive. Like something that remembers where it came from.