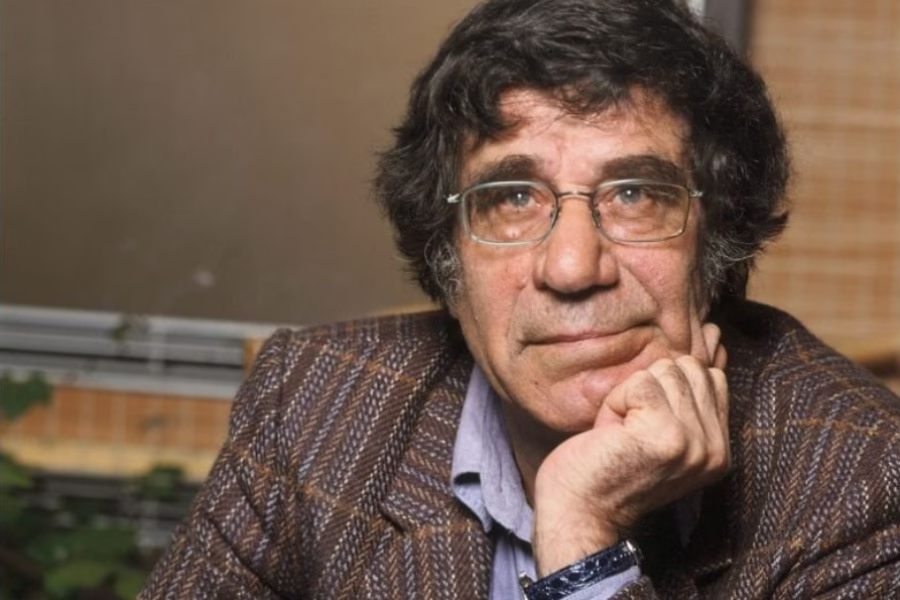

Sharp pen, sharper mind: Chraïbi made literature a weapon.

Fez – The 30th edition of the Rabat International Book Fair isn’t playing it safe. From April 18 to 27, the spotlight is on Idriss Chraïbi; a name that might not echo loudly in casual circles, but for anyone even remotely serious about literature, it lands like a thunderclap.

Born in 1926 and gone since 2007, Chraïbi wasn’t your typical writer. He was a disrupter in the most literary sense.

He wrote in French, but make no mistake, he used that language to drag colonialism, patriarchy, and hypocrisy into the daylight.

His work didn’t pander. It challenged, interrogated, and, quite frankly, annoyed the right people.

This year’s tribute feels like a quiet but firm acknowledgment: Chraïbi mattered. Not just to Moroccan literature, but to the broader, messier, and more interesting world of postcolonial thought.

He’s part of that small club of authors who didn’t just write stories, they rewired the way we think about identity, power, and belonging.

His most iconic novels “The Simple Past” and “Mother Comes of Age” aren’t books you finish and shelve.

They linger, they scratch at the back of your mind. These aren’t comforting narratives wrapped in nostalgia; they’re sharp tools aimed directly at the myths we like to tell ourselves.

Chraïbi didn’t write to preserve the past, he wrote to indict it.

Through his characters, often torn, rebellious, deeply human he peeled back the sanitized surface of society to expose the contradictions underneath.

And while some labeled him “too harsh” or “too Western,” what he really was is honest. Painfully so.

Chraïbi’s influence remains powerful, not because he played nice, but because he truly didn’t.

He offered a new literary blueprint for what it means to be Moroccan, to be diasporic, to be caught between languages and loyalties.

Even today, scholars revisit his work, readers discover him with wide eyes, and Morocco finally seems ready to claim him with pride.

This tribute at the Rabat Book Fair isn’t just a celebration of an author, it’s a reminder.

That literature, when done right, should stir the pot, ask dangerous questions, and, if necessary, burn a few bridges.

Chraïbi did all that in French. Somehow, it still felt unmistakably Moroccan.

Read also: From Pen to Palette: Rabat Museum Spotlights Tahar Ben Jelloun’s Painting Genius