In rediscovering an ancient astrolabe, Mohamed Hilout found a way to connect modern minds to medieval skies.

Fez– In the quiet arc of Morocco’s scientific memory, few names have traveled as far as that of Mohamed Pascal Hilout.

Born in 1952 near Taza, a city that once stood at the crossroads of Arab, Amazigh, and Andalusian knowledge, Hilout grew up speaking multiple languages without fully realizing their intellectual power. “All Moroccans are polyglots by default,” he said in an interview with Morocco World News.

As a boy, he learned French and Darija. As a teenager in Fez, he added German to his list. Then, like many gifted students of his generation, he left the country, pursuing studies in Germany under a university scholarship.

Hilout’s early career unfolded far from the humanities. He worked in computing and transport systems for France’s national railways.

But his mind, shaped by a fascination with logic and form, never left the questions of time, space, and structure. It was only in 1995, well into his professional life, that a meeting with an amateur astronomy association triggered a deeper transformation. The sky, it turned out, still held unfinished business.

That interest turned into a project that would consume decades. What began as casual observation evolved into serious research.

He found himself returning not just to stars and planets, but to the instruments that had once helped humanity locate itself in the universe.

Chief among them: the astrolabe. Once a prized possession of scholars, navigators, and rulers, the astrolabe offered a window into the scientific imagination of ancient civilizations, Babylonians, Greeks, Persians, Arabs, Andalusians, and North Africans.

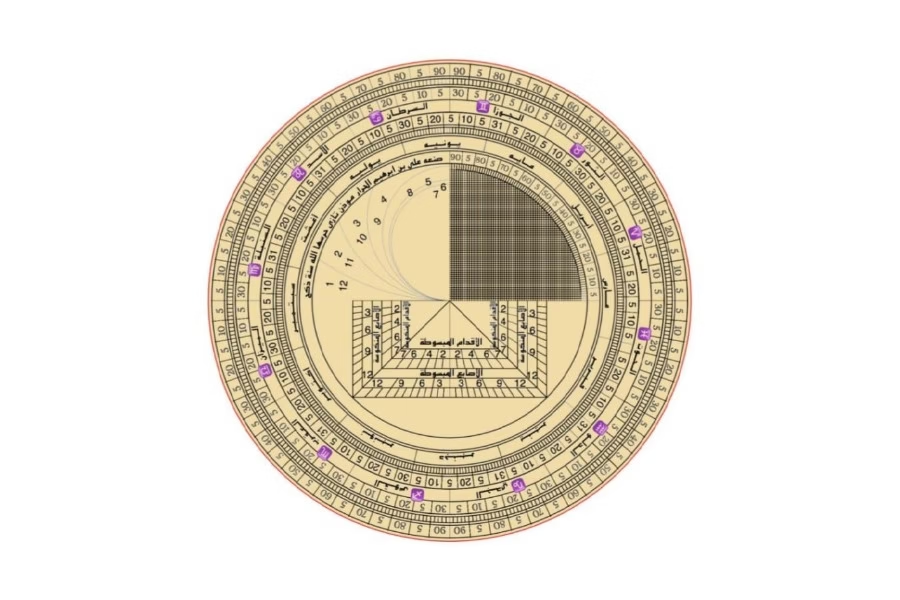

Hilout approached the astrolabe as a systems analyst might approach a machine. He began reconstructing their logic using software he developed himself, digitally modeling these complex instruments, then engraving them with a laser cutter to create precise replicas.

By combining programming and historical research, he found a way to translate centuries-old geometry into a language he could manipulate.

His work gave shape not just to the object itself, but to the worldviews encoded within it. “I’m not a craftsman or a physicist,” he says. “I’m someone who builds bridges between ideas.”

One such object would change everything. In 2022, Hilout’s attention was drawn to a 14th-century universal astrolabe, crafted in Taza by a maker named Ali ben Brahim al-Harrar.

Forgotten for centuries, it had survived in the collections of Oxford’s History of Science Museum. For Hilout, the discovery was less about pride than continuity: proof that the city of his birth had once contributed to the global development of astronomical science.

This instrument became the centerpiece of his 2024 book, “Astrolabes Through Historical Texts and Artefacts”, written in Arabic and aimed at a new generation of Arab readers.

In it, Hilout does something rare, he introduces, for the first time in Arabic, the earliest known technical description of a classical astrolabe, written by the Alexandrian scholar John Philoponus in the sixth century.

He supports it with illustrations generated through his own software and devotes an entire chapter to the rediscovered Taza astrolabe, complete with historical analysis and technical diagrams.

He followed this work with a second book in early 2025, a translation and study of kitab fi alhaya”, the 12th-century Andalusian treatise by Nur al-Din al-Bitruji.

In it, Hilout builds a pedagogical narrative tracing the evolution of cosmological thinking from Pythagoras and Plato to Ibn al-Shatir and al-Qushji.

Alongside the book, he launched an online educational platform, providing a detailed visual archive of astronomical knowledge across Greco-Arabic, Persian, and Ottoman traditions.

But Hilout’s project is not confined to philology or restoration. At its core lies a critical argument about the trajectory of scientific history.

He contends that Aristotelian cosmology, with its fixed spheres and geocentric worldview, dominated not because it was the most accurate model, but because it served religious and political purposes across empires.

“Aristotle’s model was beautiful, but it became a golden cage,” he says. “It trapped scientific thought in a closed system.”

This framework, he believes, stifled the development of physics and rational mechanics for centuries in both East and West.

Lost in this eclipse were earlier, more dynamic hypotheses, like the Pythagorean view of Earth’s rotation or Archimedes’ vision of mechanical laws, ideas that could have led to scientific revolutions far earlier than the Renaissance.

It is not enough, in his view, to celebrate Islamic astronomy for its technical achievements. The real task lies in re-examining the philosophical choices that shaped scientific inquiry.

Why, he asks, did so many civilizations adopt models that were elegant, but fundamentally flawed? Why were dynamic systems resisted in favor of idealized geometries? These are the questions he wants to see addressed in curricula across Morocco and the wider Arab world.

His critique extends to contemporary pedagogy. Despite Morocco’s long and rich scientific past, Hilout sees little evidence of serious engagement with its complexities.

University-level teaching, he says, still relies on outdated assumptions that fail to explore the historical alternatives to Aristotelian thought.

“We teach astronomy without context,” he says. “We show the stars but not the ideas behind how we understand them.”

Yet Hilout does not advocate nostalgia. For him, the astrolabe is not a relic, but a teaching tool. Constructing one, he believes, is an excellent way to teach students practical geometry, astronomy, and intellectual history simultaneously.

He envisions a classroom where students learn to build astrolabes not to mystify the past, but to understand it as a living intellectual system.

Even so, the astrolabe retains a kind of aura. Its Kufic inscriptions, abstract beauty, and mathematical elegance set it apart from the cold utility of modern tools.

Unlike smartphones, which are ubiquitous and quickly obsolete, astrolabes were rare and refined, objects of ceremony and authority, used by caliphs, scholars, and navigators alike. Their appeal was not only scientific, but symbolic.

Though some today try to link the astrolabe with astrology, Hilout makes a careful distinction.

He does not dismiss the fact that astrology played a role across ancient cultures. But he stresses that in the Islamic context, the astrolabe was primarily used for precise scientific tasks: determining prayer times, tracking celestial events, and calculating coordinates.

“It was a clock, a compass, and a calculator all at once,” he says.

Hilout has no interest in predicting the future. For him, the stars are not symbols of fate, but testimonies to human curiosity.

His work invites others to look up, not to dream of destiny, but to rediscover the questions that shaped the minds of those who did.

Read also: Egypt’s $30 Million Project to Reimagine a 4,600-Year-Old Wonder