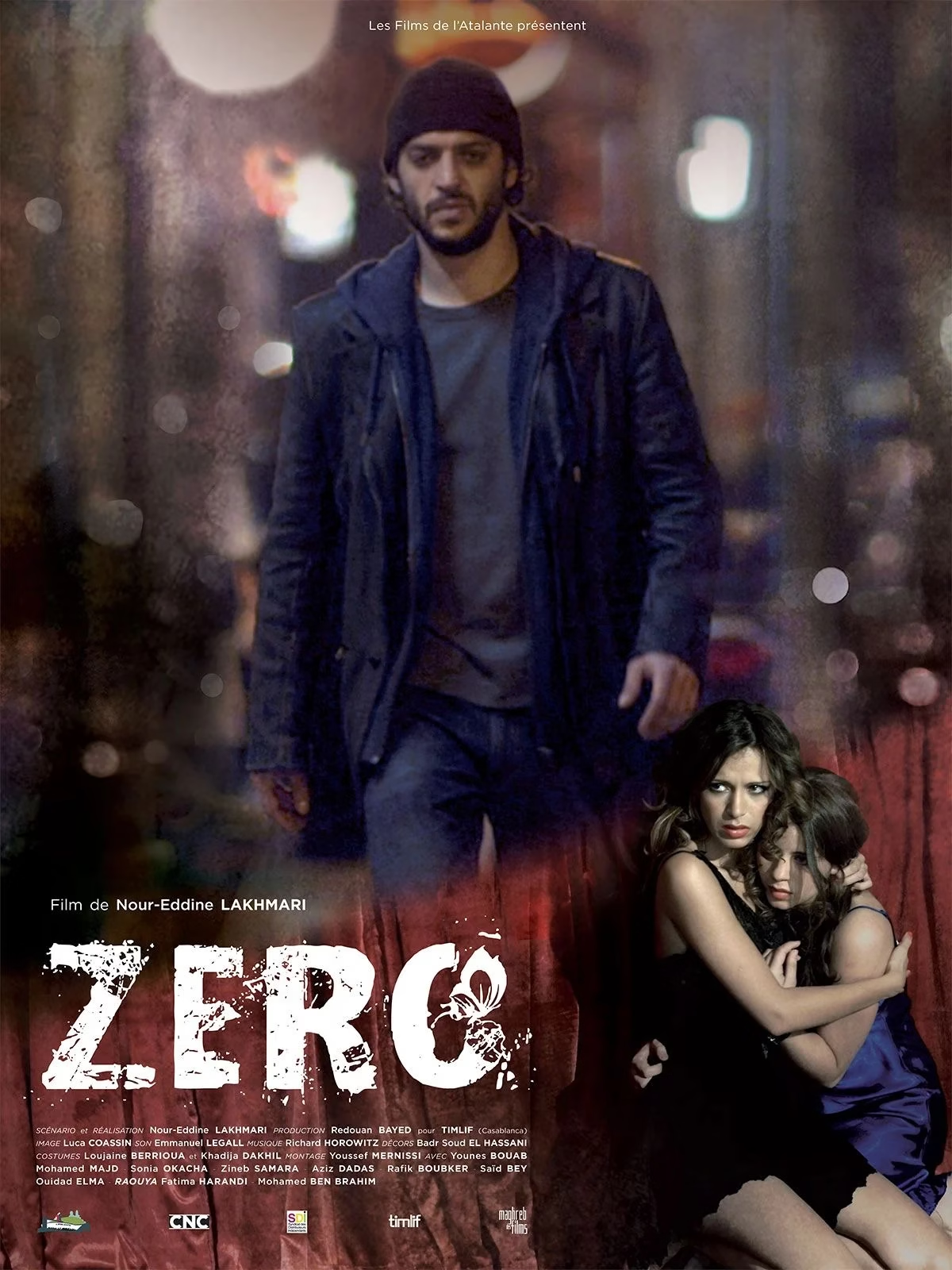

Fez — Long before gritty streaming dramas became the rage, Moroccan director Nour‑Eddine Lakhmari premiered Zero (2012), a rain‑slick, neon‑lit dive into Casablanca’s moral twilight. It’s wa a movie that explored the liminal space between morality and immorality; following Zero the anti-hero of the story.

Thirteen years on, the film still pulses through local pop culture—quoted by rappers, screened in the movies, and hailed by critics as the country’s first true neo‑noir.

A cop named ‘Zero’ and a city on edge

Younes Bouab plays Amine Bertale, a jaded police officer whose nickname “Zero” reflects his stalled career and eroding conscience. It also suggests that he’s in a morally neutral position, neither good nor bad.

He is like number 0: sits in the middle between positive and negative numbers. Zero’s story is that of someone who cannot fully be good or the other way: corrupt.

Between whiskey shots and accidental heroics, he stumbles onto a missing‑girl case that drags him through brothels, back alleys, and his own past.

He also discovers the corrupt core of Casablanca’s elite, which is something that he shouldn’t have, given that he’s been warned not to stick his nose too deep.

Casablanca itself becomes an accomplice—rainy, restless, and shot in desaturated blues by cinematographer Luca Coassin. (imdb.com)

Making Casablanca a noir capital

Zero followed Lakhmari’s festival hit “Casanegra” and cemented his informal “Casablanca Trilogy.”

The director cast non‑professionals alongside stage veterans, recorded live street sound, and worked with composer Richard Horowitz to layer jazzy motifs over Arabic percussion. The director’s innovative approach extended beyond conventional filmmaking, weaving a rich tapestry of authenticity and artistic vision.

By deliberately choosing non-professional actors to perform alongside seasoned stage veterans, he cultivated a unique dynamic that brought raw, unfiltered emotion to the screen, complementing the polished performances of the experienced cast. This blend created a compelling realism, blurring the lines between fiction and documentary.

Furthermore, the commitment to capturing the genuine pulse of the city was evident in the decision to record live street sound. This wasn’t merely background noise; it was an integral character in itself, imbuing the film with the cacophony and rhythm of daily life, grounding the narrative in a tangible reality.

The bustling markets, the distant calls to prayer, the chatter of passersby—all contributed to an immersive auditory experience that transported the audience directly into the heart of Morocco.

The collaboration with composer Richard Horowitz was another stroke of genius that elevated the film’s artistic merit. Horowitz’s ability to seamlessly layer jazzy motifs over traditional Arabic percussion created a groundbreaking soundscape that was both evocative and culturally resonant.

The music became a character in itself, accentuating the emotional nuances of each scene and enhancing the overall neo-noir atmosphere. This meticulous attention to detail in casting, sound design, and musical composition ultimately cemented the film’s status as a pioneering work in Moroccan cinema.

In interviews, Lakhmari says he aimed to capture “the heartbeat under the chaos.”

Awards and box‑office impact

At Morocco’s 14th National Film Festival in Tangier, Zero won the Grand Prize plus four acting and technical trophies. It went on to log more than 180,000 domestic admissions, topping the local box office for 15 weeks—a record for an R‑rated Moroccan drama at the time.

Why it still resonates

Zero endures partly because it exposes institutional rot without flinching. From petty bribes to unchecked violence, the film paints a police force trapped in the same cycles of poverty and powerlessness that plague the citizens it should protect—echoing Morocco’s ongoing public debate over law‑enforcement reform.

Lakhmari’s screenplay also probes masculinity in crisis. Beneath Zero’s swagger and violence lies acute loneliness, an identity crisis familiar to many young men navigating stalled upward mobility. His unraveling becomes a mirror for an audience grappling with shifting social expectations and economic uncertainty.

Finally, the movie turns Casablanca into a full‑fledged character. Rooftops, tramway lines, and port‑side neon frame the city as both playground and prison, lending Casablanca the brooding gravitas of classic noir metropolises and affirming its place in global cinema’s urban imagination.

Where to stream

Rights issues keep Zero off global giants like Netflix, but it cycles through MENA‑region platforms such as Shahed and pops up in festival retrospectives. Film buffs can also catch restored prints at the Cinémathèque de Tanger’s annual “Nuit du Noir.”

The legacy

For many cinephiles, Zero marked the moment Moroccan cinema shook off colonial‑era nostalgia and dove head‑first into present‑day unease.

As Lakhmari prepares a new dystopian thriller set in 2030 Casablanca, Zero continues to teach that the city’s harsh glare can double as a spotlight on uncomfortable truths.