Rabat – Premiering August 3 on HBO and now streaming on Max, Margaret Brown’s four-part documentary revisits the brutal 1991 killing of four teenage girls in an Austin yogurt shop, execution-style murders that remain officially unsolved more than three decades later .

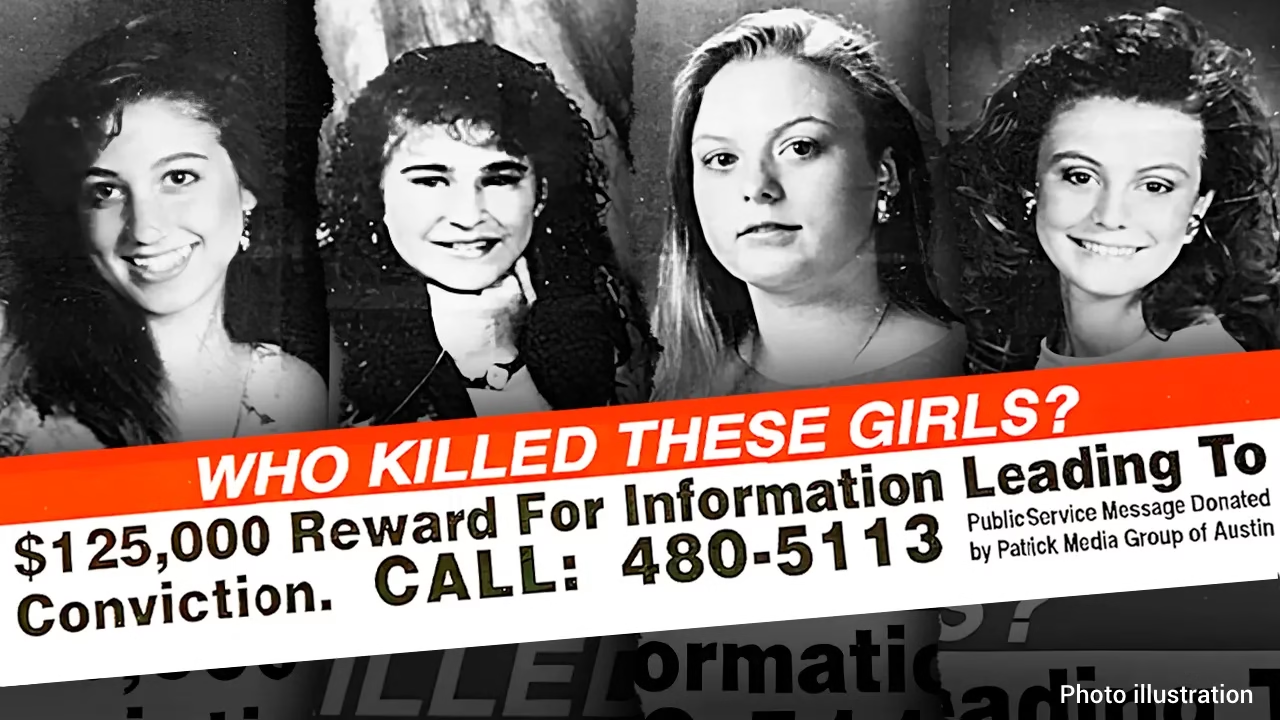

On December 6, 1991, Amy Ayers (13), Eliza Thomas (17), and sisters Jennifer (17) and Sarah Harbison (15) were found bound, shot, and burned inside an “I Can’t Believe It’s Yogurt!” shop in North Austin, Texas.

Firefighters first thought they were responding to a simple fire at the yogurt shop, but were met with a horrifying scene: the bodies of the four teenage girls.

They had been tied up, shot execution-style, and set on fire. The scene was so gruesome that first responders still speak about it with visible discomfort. Despite multiple arrests and confessions, DNA evidence later contradicted convictions, and charges were dismissed in 2009.

The crime remains unresolved.

Brown’s docuseries combines archived news footage, unused 2009 interviews by Claire Huie, a former aspiring filmmaker, and emotionally raw conversations with the victims’ families, investigators, and wrongful conviction survivors.

“There’s never closure, you learn how to live alongside it, but there’s never closure,” Said Brown, quoting family members who have carried grief for decades.

One of the series’ most haunting voices is Barbara Ayers‑Wilson, mother of Jennifer and Sarah. Her on‑screen recollection of the night she lost her daughters anchors the emotional core of the series. Her raw regret lingers in a line that feels like a refrain, “You just have all of these regrets of not protecting them.”

Behind the scenes, the emotional toll was staggering. As Brown revealed to Variety crime‑scene photos were so disturbing that her editorial team refused to look at them, warning they’d “haunt you for the rest of your life.”

A24 even arranged therapy sessions for staff. One crew member collapsed from the weight of the material. “It was just so hard bearing witness…” Brown said.

Unlike many true‑crime shows, Brown refuses sensationalism. Instead, she probes systemic failures: coerced confessions, flawed policing, especially the role of Detective Hector Polanco, later reprimanded for misconduct, and how media pressure shaped public perception.

Ultimately, “The Yogurt Shop Murders” is more than a true‑crime doc. It’s a profoundly human portrait of grief, institutional failure, and unresolved legacy.

It doesn’t promise closure; it challenges us to live with ambiguity and witness the long‑term impact of a crime that has never found resolution.