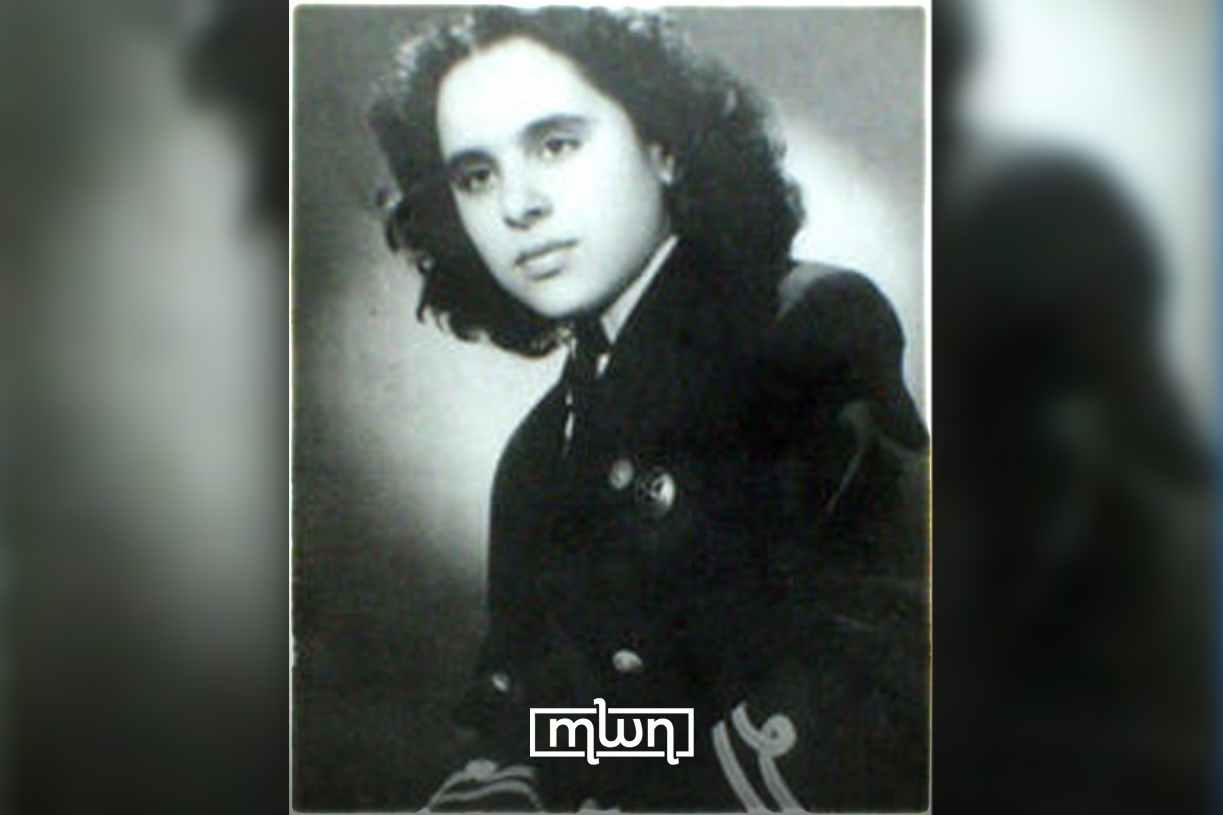

How was the life of the first Arab Moroccan female to become a pilot?

Fez – Touria Chaoui was born on December 14, 1936, in Fez, a time and place where flying a plane was not just unusual for women, it was unthinkable.

But she thought otherwise. In a deeply patriarchal society, and long before women’s empowerment became a national slogan, Touria became the first Moroccan and Arab woman to earn a pilot’s license. And she did it – at just 16.

She grew up in a modest, educated household. Her father, Abderrahmane Chaoui, was a journalist and a theater director, and a constant supporter of her dreams.

It was he who introduced her to Arabic grammar, Islamic jurisprudence, and history from a young age. But it was her love for machines, taking them apart, rebuilding them, that first hinted she wasn’t like other children.

Her fascination with flying was born early. Suffering from a chest illness in childhood, her father once took her on a plane ride as a form of air therapy.

That moment, more than any lesson or book, set her course. Planes became her passion, not in a poetic sense, but with a mechanical and intellectual curiosity.

Touria wasn’t only interested in aviation. She had many talents: she acted in a French film at 13, wrote poetry, loved literature, and was drawn to theater.

In 1948, she performed in “The Seventh Door”, a symbolic film about knowledge, temptation, and discovery, shot in Fez, alongside her father.

It was a fitting metaphor for her own life: crossing thresholds others feared.

In 1950, fresh out of high school, she joined the Tit Mellil aviation school near Casablanca, an unconventional choice for a Moroccan girl in the 1950s.

Her family moved with her, fully aware of the backlash they would face. But she trained relentlessly and passed her flight test on October 17, 1951, navigating poor weather conditions and flying 3,000 meters above ground.

She was just 16. Her first flight was between Casablanca and Rabat, alone, in a Piper plane.

This was not just a national achievement; it resonated far beyond Morocco. Touria was celebrated by King Mohammed V, honored by Princesses Lalla Aicha and Lalla Malika, praised by nationalist leaders like Allal al-Fassi, and even recognized by the famed French aviator Jacqueline Auriol. She became a national icon, but also a threat.

At the time, Morocco was still under French rule. Touria didn’t just fly planes, she used them for political resistance.

In 1955, as King Mohammed V returned from exile, she flew above the welcoming procession, dropping leaflets calling for independence. Her activism placed her squarely in the crosshairs of colonial forces.

She survived multiple assassination attempts: a bomb outside her home in 1954, gunfire at her and her father that same year, and another shooting by French officers in 1955, narrowly escaped thanks to a crowd that shielded her.

But on March 1, 1956, just one day before Morocco’s official independence, Touria Chaoui was shot dead outside her home.

She was 19. Moroccan intelligence reports later linked her killing to a secret militia, with rumors that she was targeted both for her political role and her refusal to marry a powerful figure.

Touria’s death was not just a personal tragedy; it was a silencing of potential. A young woman who had mastered the skies, embraced modernity, and dared to dream for her country.

Her story isn’t merely about aviation; it’s about a woman who stood at the intersection of national struggle, personal ambition, and societal transformation.

Even decades later, her name carries a quiet force. She wasn’t just a pioneer. She was proof that courage isn’t always loud.

Sometimes, it’s a teenage girl in a flight suit, steering history through turbulence.

Read also: Why Moroccans Still Hold Sugar So Dear